Blavatsky H.P. - An Unsolved Mystery: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

Mme. de Lassa performed upon the piano or conversed from group to group in a way that seemed to be delightful, while M. de Lassa walked about or sat in his insignificant, unconcerned way, saying a word now and then, but seeming to shun everything that was conspicuous. Servants handed about refreshments, ices, cordials, wines, etc., and Delessert could have fancied himself [to have] dropped in upon a quite modest evening entertainment, altogether en règle, but for one or two noticeable circumstances which his observant eyes quickly took in. | Mme. de Lassa performed upon the piano or conversed from group to group in a way that seemed to be delightful, while M. de Lassa walked about or sat in his insignificant, unconcerned way, saying a word now and then, but seeming to shun everything that was conspicuous. Servants handed about refreshments, ices, cordials, wines, etc., and Delessert could have fancied himself [to have] dropped in upon a quite modest evening entertainment, altogether en règle, but for one or two noticeable circumstances which his observant eyes quickly took in. | ||

Except when their host or hostess was within hearing, the guests conversed together in low tones, rather mysteriously, and with not quite so much laughter as is usual on such occasions. At intervals a very tall and dignified footman would come to a guest, and, with a profound bow, present him a card on a silver salver. The guest would {{Page aside|153}} then go out, preceded by the solemn servant, but when he or she returned to the salon—some did not return at all—they invariably wore a dazed or puzzled look, were confused, astonished, frightened, or amused. All this was so unmistakably genuine, and de Lassa and his wife seemed so unconcerned amidst it all, not to say distinct from it all, that Delessert could not avoid being forcibly struck and considerably puzzled. | Except when their host or hostess was within hearing, the guests conversed together in low tones, rather mysteriously, and with not quite so much laughter as is usual on such occasions. At intervals a very tall and dignified footman would come to a guest, and, with a profound bow, present him a card on a silver salver. The guest would {{Page aside|153}}then go out, preceded by the solemn servant, but when he or she returned to the salon—some did not return at all—they invariably wore a dazed or puzzled look, were confused, astonished, frightened, or amused. All this was so unmistakably genuine, and de Lassa and his wife seemed so unconcerned amidst it all, not to say distinct from it all, that Delessert could not avoid being forcibly struck and considerably puzzled. | ||

Two or three little incidents, which came under Delessert’s own immediate observation, will suffice to make plain the character of the impressions made upon those present. A couple of gentlemen, both young, both of good social condition, and evidently very intimate friends, were conversing together and tutoying one another at a great rate, when the dignified footman summoned Alphonse. He laughed gaily. “Tarry a moment, cher Auguste,” said he, “and thou shalt know all the particulars of this wonderful fortune!” “Eh bien!” responded Auguste, “may the oracle’s mood be propitious!” A minute had scarcely elapsed when Alphonse returned to the salon. His face was white and bore an appearance of concentrated rage that was frightful to witness. He came straight to Auguste, his eyes flashing, and bending his face toward his friend, who changed colour and recoiled, he hissed out, “Monsieur Lefébure, vous êtes un lâche!” “Very well, Monsieur Meunier,” responded Auguste, in the same low tone, “to-morrow morning at six o’clock!” “It is settled, false friend, execrable traitor! À la mort!” rejoined Alphonse, walking off. “Cela va sans dire!” muttered Auguste, going towards the hat-room. | Two or three little incidents, which came under Delessert’s own immediate observation, will suffice to make plain the character of the impressions made upon those present. A couple of gentlemen, both young, both of good social condition, and evidently very intimate friends, were conversing together and tutoying one another at a great rate, when the dignified footman summoned Alphonse. He laughed gaily. “Tarry a moment, cher Auguste,” said he, “and thou shalt know all the particulars of this wonderful fortune!” “Eh bien!” responded Auguste, “may the oracle’s mood be propitious!” A minute had scarcely elapsed when Alphonse returned to the salon. His face was white and bore an appearance of concentrated rage that was frightful to witness. He came straight to Auguste, his eyes flashing, and bending his face toward his friend, who changed colour and recoiled, he hissed out, “Monsieur Lefébure, vous êtes un lâche!” “Very well, Monsieur Meunier,” responded Auguste, in the same low tone, “to-morrow morning at six o’clock!” “It is settled, false friend, execrable traitor! À la mort!” rejoined Alphonse, walking off. “Cela va sans dire!” muttered Auguste, going towards the hat-room. | ||

A diplomatist of distinction, representative at Paris of a neighboring state, an elderly gentleman of superb aplomb and most commanding appearance, was summoned to the oracle by the bowing footman. After being absent about five minutes he returned, and immediately made his way through the press to M. de Lassa, who was standing not far from the fireplace, with his hands in his pockets, and a look of utmost indifference upon his face. Delessert standing near, watched the interview with eager interest. “I am {{Page aside|154}} exceedingly sorry,” said General Von—,“to have to absent myself so soon from your interesting salon, M. de Lassa, but the result of my séance convinces me that my dispatches have been tampered with.” “I am sorry,” responded M. de Lassa, with an air of languid but courteous interest, “I hope you may be able to discover which of your servants has been unfaithful.” “I am going to do that now,” said the General, adding, in significant tones, “I shall see that both he and his accomplices do not escape severe punishment.” “That is the only course to pursue, Monsieur le Comte.” The ambassador stared, bowed, and took his leave with a bewilderment on his face that was beyond the power of his tact to control. | A diplomatist of distinction, representative at Paris of a neighboring state, an elderly gentleman of superb aplomb and most commanding appearance, was summoned to the oracle by the bowing footman. After being absent about five minutes he returned, and immediately made his way through the press to M. de Lassa, who was standing not far from the fireplace, with his hands in his pockets, and a look of utmost indifference upon his face. Delessert standing near, watched the interview with eager interest. “I am {{Page aside|154}}exceedingly sorry,” said General Von—,“to have to absent myself so soon from your interesting salon, M. de Lassa, but the result of my séance convinces me that my dispatches have been tampered with.” “I am sorry,” responded M. de Lassa, with an air of languid but courteous interest, “I hope you may be able to discover which of your servants has been unfaithful.” “I am going to do that now,” said the General, adding, in significant tones, “I shall see that both he and his accomplices do not escape severe punishment.” “That is the only course to pursue, Monsieur le Comte.” The ambassador stared, bowed, and took his leave with a bewilderment on his face that was beyond the power of his tact to control. | ||

In the course of the evening M. de Lassa went carelessly to the piano, and, after some indifferent vague preluding, played a remarkably effective piece of music, in which the turbulent life and buoyancy of bacchanalian strains melted gently, almost imperceptibly away, into a sobbing wail of regret and languor, and weariness and despair. It was beautifully rendered, and made a great impression upon the guests, one of whom, a lady, cried, “How lovely, how sad! Did you compose that yourself, M. de Lassa?” He looked towards her absently for an instant, then replied: “I? Oh, no! That is merely a reminiscence, madame.” “Do you know who did compose it, M. de Lassa?” enquired a virtuoso present. “I believe it was originally written by Ptolemy Auletes, the father of Cleopatra,” said M. de Lassa, in his indifferent, musing way, “but not in its present form. It has been twice re-written to my knowledge; still, the air is substantially the same.” “From whom did you get it, M. de Lassa, if I may ask?” persisted the gentleman. “Certainly! certainly! The last time I heard it played was by Sebastian Bach; but that was Palestrina’s—the present—version. I think I prefer that of Guido of Arezzo—it is ruder, but has more force. I got the air from Guido himself.” “You—from—Guido!” cried the astonished gentleman, “Yes, monsieur,” answered de Lassa, rising from the piano with his usual indifferent air. “Mon Dieu!” cried the virtuoso, putting his hand to his head after the manner of {{Page aside|155}} Mr. Twemlow, “Mon Dieu! that was in Anno Domini 1022!” “A little later than that—July 1031, if I remember rightly,” courteously corrected M. de Lassa. | In the course of the evening M. de Lassa went carelessly to the piano, and, after some indifferent vague preluding, played a remarkably effective piece of music, in which the turbulent life and buoyancy of bacchanalian strains melted gently, almost imperceptibly away, into a sobbing wail of regret and languor, and weariness and despair. It was beautifully rendered, and made a great impression upon the guests, one of whom, a lady, cried, “How lovely, how sad! Did you compose that yourself, M. de Lassa?” He looked towards her absently for an instant, then replied: “I? Oh, no! That is merely a reminiscence, madame.” “Do you know who did compose it, M. de Lassa?” enquired a virtuoso present. “I believe it was originally written by Ptolemy Auletes, the father of Cleopatra,” said M. de Lassa, in his indifferent, musing way, “but not in its present form. It has been twice re-written to my knowledge; still, the air is substantially the same.” “From whom did you get it, M. de Lassa, if I may ask?” persisted the gentleman. “Certainly! certainly! The last time I heard it played was by Sebastian Bach; but that was Palestrina’s—the present—version. I think I prefer that of Guido of Arezzo—it is ruder, but has more force. I got the air from Guido himself.” “You—from—Guido!” cried the astonished gentleman, “Yes, monsieur,” answered de Lassa, rising from the piano with his usual indifferent air. “Mon Dieu!” cried the virtuoso, putting his hand to his head after the manner of {{Page aside|155}}Mr. Twemlow, “Mon Dieu! that was in Anno Domini 1022!” “A little later than that—July 1031, if I remember rightly,” courteously corrected M. de Lassa. | ||

At this moment the tall footman bowed before M. Delessert, and presented the salver containing the card. Delessert took it and read: “On vous accorde trente-cinq secondes, M. Flabry, tout au plus!” Delessert followed the footman from the salon across the corridor. The footman opened the door of another room and bowed again, signifying that Delessert was to enter. “Ask no questions,” he said briefly; “Sidi is mute.” Delessert entered the room and the door closed behind him. It was a small room, with a strong smell of frankincense pervading it. The walls were covered completely with red hangings that concealed the windows, and the floor was felted with a thick carpet. Opposite the door, at the upper end of the room near the ceiling, was the face of a large clock; under it, each lighted by tall wax candles, were two small tables containing, the one an apparatus very like the common registering telegraph instrument, the other a crystal globe about twenty inches in diameter, set upon an exquisitely wrought tripod of gold and bronze intermingled. By the door stood Sidi, a man jet black in colour, wearing a white turban and burnous, and having a sort of wand of silver in one hand. With the other, he took Delessert by the right arm above the elbow, and led him quickly up the room. He pointed to the clock, and it struck an alarm; he pointed to the crystal. Delessert bent over, looked into it and saw—a facsimile of his own sleeping-room, everything photographed exactly. Sidi did not give him time to exclaim, but still holding him by the arm, took him to the other table. The telegraph-like instrument began to click-click. Sidi opened the drawer, drew out a slip of paper, crammed it into Delessert’s hand, and pointed to the clock, which struck again. The thirty-five seconds were expired. Sidi, still retaining hold of Delessert’s arm, pointed to the door and led him towards it. The door opened, Sidi pushed him out, the door closed, the tall footman stood there bowing, the interview with the oracle was over. Delessert glanced at {{Page aside|156}} the piece of paper in his hand. It was a printed scrap, capital letters, and read simply: “To M. Paul Delessert: The policeman is always welcome; the spy is always in danger! | At this moment the tall footman bowed before M. Delessert, and presented the salver containing the card. Delessert took it and read: “On vous accorde trente-cinq secondes, M. Flabry, tout au plus!” Delessert followed the footman from the salon across the corridor. The footman opened the door of another room and bowed again, signifying that Delessert was to enter. “Ask no questions,” he said briefly; “Sidi is mute.” Delessert entered the room and the door closed behind him. It was a small room, with a strong smell of frankincense pervading it. The walls were covered completely with red hangings that concealed the windows, and the floor was felted with a thick carpet. Opposite the door, at the upper end of the room near the ceiling, was the face of a large clock; under it, each lighted by tall wax candles, were two small tables containing, the one an apparatus very like the common registering telegraph instrument, the other a crystal globe about twenty inches in diameter, set upon an exquisitely wrought tripod of gold and bronze intermingled. By the door stood Sidi, a man jet black in colour, wearing a white turban and burnous, and having a sort of wand of silver in one hand. With the other, he took Delessert by the right arm above the elbow, and led him quickly up the room. He pointed to the clock, and it struck an alarm; he pointed to the crystal. Delessert bent over, looked into it and saw—a facsimile of his own sleeping-room, everything photographed exactly. Sidi did not give him time to exclaim, but still holding him by the arm, took him to the other table. The telegraph-like instrument began to click-click. Sidi opened the drawer, drew out a slip of paper, crammed it into Delessert’s hand, and pointed to the clock, which struck again. The thirty-five seconds were expired. Sidi, still retaining hold of Delessert’s arm, pointed to the door and led him towards it. The door opened, Sidi pushed him out, the door closed, the tall footman stood there bowing, the interview with the oracle was over. Delessert glanced at {{Page aside|156}}the piece of paper in his hand. It was a printed scrap, capital letters, and read simply: “To M. Paul Delessert: The policeman is always welcome; the spy is always in danger! | ||

Delessert was dumbfounded a moment to find his disguise detected; but the words of the tall footman, “This way, if you please, M. Flabry,” brought him to his senses. Setting his lips, he returned to the salon, and without delay sought M. de Lassa. “Do you know the contents of this?” asked he, showing the message. “I know everything, M. Delessert,” answered de Lassa, in his careless way. “Then perhaps you are aware that I mean to expose a charlatan, and unmask a hypocrite, or perish in the attempt?” said Delessert. “Cela m’est égal, monsieur,” replied de Lassa. “You accept my challenge, then?” “Oh! it is a defiance, then?” replied de Lassa, letting his eye rest a moment upon Delessert, “mais oui, je l’accepte!” And thereupon Delessert departed. | Delessert was dumbfounded a moment to find his disguise detected; but the words of the tall footman, “This way, if you please, M. Flabry,” brought him to his senses. Setting his lips, he returned to the salon, and without delay sought M. de Lassa. “Do you know the contents of this?” asked he, showing the message. “I know everything, M. Delessert,” answered de Lassa, in his careless way. “Then perhaps you are aware that I mean to expose a charlatan, and unmask a hypocrite, or perish in the attempt?” said Delessert. “Cela m’est égal, monsieur,” replied de Lassa. “You accept my challenge, then?” “Oh! it is a defiance, then?” replied de Lassa, letting his eye rest a moment upon Delessert, “mais oui, je l’accepte!” And thereupon Delessert departed. | ||

Delessert now set to work, aided by all the forces the Prefect of Police could bring to bear, to detect and expose this consummate sorcerer, whom the ruder processes of our ancestors would easily have disposed of—by combustion. Persistent enquiry satisfied Delessert that the man was neither a Hungarian nor named de Lassa; that no matter how far back his power of “reminiscence” might extend, in his present and immediate form he had been born in this unregenerate world in the toy-making city of Nuremberg; that he was noted in boyhood for his great turn for ingenious manufactures, but was very wild, and a mauvais sujet. In his sixteenth year he had escaped to Geneva and apprenticed himself to a maker of watches and instruments. Here he had been seen by the celebrated Robert Houdin, the prestidigitateur. Houdin, recognizing the lad’s talents, and being himself a maker of ingenious automata, had taken him off to Paris and employed him in his own workshops, as well as an assistant in the public performances of his amusing and curious diablerie. After staying with Houdin some years, Pflock Haslich (which was de Lassa’s right name) had gone East in the suite of a Turkish Pasha, {{Page aside|157}} and after many years’ roving, in lands where he could not be traced under a cloud of pseudonyms, had finally turned up in Venice, and come thence to Paris. | Delessert now set to work, aided by all the forces the Prefect of Police could bring to bear, to detect and expose this consummate sorcerer, whom the ruder processes of our ancestors would easily have disposed of—by combustion. Persistent enquiry satisfied Delessert that the man was neither a Hungarian nor named de Lassa; that no matter how far back his power of “reminiscence” might extend, in his present and immediate form he had been born in this unregenerate world in the toy-making city of Nuremberg; that he was noted in boyhood for his great turn for ingenious manufactures, but was very wild, and a mauvais sujet. In his sixteenth year he had escaped to Geneva and apprenticed himself to a maker of watches and instruments. Here he had been seen by the celebrated Robert Houdin, the prestidigitateur. Houdin, recognizing the lad’s talents, and being himself a maker of ingenious automata, had taken him off to Paris and employed him in his own workshops, as well as an assistant in the public performances of his amusing and curious diablerie. After staying with Houdin some years, Pflock Haslich (which was de Lassa’s right name) had gone East in the suite of a Turkish Pasha, {{Page aside|157}}and after many years’ roving, in lands where he could not be traced under a cloud of pseudonyms, had finally turned up in Venice, and come thence to Paris. | ||

Delessert next turned his attention to Mme. de Lassa. It was more difficult to get a clue by means of which to know her past life; but it was necessary in order to understand enough about Haslich. At last, through an accident, it became probable that Mme. Aimée was identical with a certain Mme. Schlaff, who had been rather conspicuous among the demi-monde of Buda. Delessert posted off to that ancient city, and thence went into the wilds of Transylvania to Medgyes. On his return, as soon as he reached the telegraph and civilization, he telegraphed the Prefect from Karcag: “Don’t lose sight of my man, nor let him leave Paris. I will run him in for you two days after I get back.” | Delessert next turned his attention to Mme. de Lassa. It was more difficult to get a clue by means of which to know her past life; but it was necessary in order to understand enough about Haslich. At last, through an accident, it became probable that Mme. Aimée was identical with a certain Mme. Schlaff, who had been rather conspicuous among the demi-monde of Buda. Delessert posted off to that ancient city, and thence went into the wilds of Transylvania to Medgyes. On his return, as soon as he reached the telegraph and civilization, he telegraphed the Prefect from Karcag: “Don’t lose sight of my man, nor let him leave Paris. I will run him in for you two days after I get back.” | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

In the morning he came to the office in a state of extreme dejection. He was completely unnerved. In relating to a brother inspector what had occurred, he said: “That man can do what he promises, I am doomed!” | In the morning he came to the office in a state of extreme dejection. He was completely unnerved. In relating to a brother inspector what had occurred, he said: “That man can do what he promises, I am doomed!” | ||

He said that he thought he could make a complete case out against Haslich alias de Lassa, but could not do so w without seeing the Prefect, and getting instructions. He would {{Page aside|158}} tell nothing in regard to his discoveries in Buda and in Transylvania—said that he was not at liberty to do so—and repeatedly exclaimed: “Oh! if M. le Préfet were only here!” He was told to go to the Prefect at Cherbourg, but refused, upon the ground that his presence was needed in Paris. He time and again averred his conviction that he was a doomed man, and showed himself both vacillating and irresolute in his conduct, and extremely nervous. He was told that he was perfectly safe, since de Lassa and all his household were under constant surveillance; to which he replied; “You do not know the man.” An inspector was detailed to accompany Delessert, never lose sight of him night and day, and guard him carefully; and proper precautions were taken in regard to his food and drink, while the guards watching de Lassa were doubled. | He said that he thought he could make a complete case out against Haslich alias de Lassa, but could not do so w without seeing the Prefect, and getting instructions. He would {{Page aside|158}}tell nothing in regard to his discoveries in Buda and in Transylvania—said that he was not at liberty to do so—and repeatedly exclaimed: “Oh! if M. le Préfet were only here!” He was told to go to the Prefect at Cherbourg, but refused, upon the ground that his presence was needed in Paris. He time and again averred his conviction that he was a doomed man, and showed himself both vacillating and irresolute in his conduct, and extremely nervous. He was told that he was perfectly safe, since de Lassa and all his household were under constant surveillance; to which he replied; “You do not know the man.” An inspector was detailed to accompany Delessert, never lose sight of him night and day, and guard him carefully; and proper precautions were taken in regard to his food and drink, while the guards watching de Lassa were doubled. | ||

On the morning of the third day, Delessert, who had been staying chiefly indoors, avowed his determination to go at once and telegraph to M. le Préfet to return immediately. With this intention he and his brother-officer started out. Just as they got to the corner of the Rue de Lancry and the Boulevard, Delessert stopped suddenly and put his hand to his forehead. | On the morning of the third day, Delessert, who had been staying chiefly indoors, avowed his determination to go at once and telegraph to M. le Préfet to return immediately. With this intention he and his brother-officer started out. Just as they got to the corner of the Rue de Lancry and the Boulevard, Delessert stopped suddenly and put his hand to his forehead. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

As soon as Delessert was sent to the hospital, his brother-inspector hurried to the Central Office, and de Lassa, together with his wife and every one connected with the establishment, were at once arrested. De Lassa smiled contemptuously as they took him away. “I knew you were coming; I prepared for it. You will be glad to release me again.” | As soon as Delessert was sent to the hospital, his brother-inspector hurried to the Central Office, and de Lassa, together with his wife and every one connected with the establishment, were at once arrested. De Lassa smiled contemptuously as they took him away. “I knew you were coming; I prepared for it. You will be glad to release me again.” | ||

It was quite true that de Lassa had prepared for them. {{Page aside|159}} When the house was searched, it was found that every paper had been burned, the crystal globe was destroyed, and in the room of the séances was a great heap of delicate machinery broken into indistinguishable bits. “That cost me 200,000 francs,” said de Lassa, pointing to the pile, “but it has been a good investment.” The walls and floors were ripped out in several places, and the damage to the property was considerable. In prison neither de Lassa nor his associates made any revelations. The notion that they had something to do with Delessert’s death was quickly dispelled, in a legal point of view, and all the party but de Lassa were released. He was still detained in prison, upon one pretext or another, when one morning he was found hanging by a silk sash to the cornice of the room where he was confined—dead. The night before, it was afterwards discovered, “Madame” de Lassa had eloped with a tall footman, taking the Nubian Sidi with them. | It was quite true that de Lassa had prepared for them. {{Page aside|159}}When the house was searched, it was found that every paper had been burned, the crystal globe was destroyed, and in the room of the séances was a great heap of delicate machinery broken into indistinguishable bits. “That cost me 200,000 francs,” said de Lassa, pointing to the pile, “but it has been a good investment.” The walls and floors were ripped out in several places, and the damage to the property was considerable. In prison neither de Lassa nor his associates made any revelations. The notion that they had something to do with Delessert’s death was quickly dispelled, in a legal point of view, and all the party but de Lassa were released. He was still detained in prison, upon one pretext or another, when one morning he was found hanging by a silk sash to the cornice of the room where he was confined—dead. The night before, it was afterwards discovered, “Madame” de Lassa had eloped with a tall footman, taking the Nubian Sidi with them. | ||

De Lassa’s secrets died with him. | De Lassa’s secrets died with him. | ||

{{HPB-CW-separator}} | {{HPB-CW-separator}} | ||

{{HPB-CW-comment|[In the next issue of the Spiritual Scientist, namely, December 2, 1875, p. 151, the following Editorial Note was published:]}} | {{HPB-CW-comment|[In the next issue of the Spiritual Scientist, namely, December 2, 1875, p. 151, the following Editorial Note was published:]}} | ||

| Line 74: | Line 73: | ||

{{HPB-CW-separator}} | {{HPB-CW-separator}} | ||

{{HPB-CW-comment|[In the same issue of the Spiritual Scientist, on page 147, there appeared the following letter to the Editor which throws further light upon this remarkable story:]}} | {{HPB-CW-comment|[In the same issue of the Spiritual Scientist, on page 147, there appeared the following letter to the Editor which throws further light upon this remarkable story:]}} | ||

Revision as of 09:05, 5 December 2024

151

AN UNSOLVED MYSTERY

The circumstances attending the sudden death of M. Delessert, inspector of the Police de Sûreté, seems to have made such an impression upon the Parisian authorities that they were recorded in unusual detail. Omitting all particulars except what are necessary to explain matters, we reproduce here the undoubtedly strange history.

In the fall of 1861 there came to Paris a man who called himself Vic de Lassa, and was so inscribed upon his passport. He came from Vienna, and said he was a Hungarian, who owned estates on the borders of the Banat, not far from Zenta. He was a small man, aged thirty-five, with pale and mysterious face, long blonde hair, a vague, wandering blue eye, and a mouth of singular firmness. He dressed carelessly and ineffectively, and spoke and talked without much empressement. His companion, presumably his wife, on the other hand, ten years younger than himself, was a strikingly beautiful woman, of that dark, rich, velvety, luscious, pure Hungarian type which is so nigh akin to the gipsy blood. At the theatres, on the Bois, at the cafés, on the boulevards, and everywhere that idle Paris disports itself, Madame Aimée de Lassa attracted great attention and made a sensation.

They lodged in luxurious apartments on the Rue Richelieu, frequented the best places, received good company, entertained handsomely, and acted in every way as if possessed of considerable wealth. Lassa had always a good balance chez Schneider, Reuter et Cie., the Austrian Bankers in Rue de Rivoli, and wore diamonds of conspicuous lustre.

How did it happen then, that the Prefect of Police saw fit to suspect Monsieur and Madame de Lassa, and detailed Paul Delessert, one of the most rusé inspectors of the force, to “pipe” him? The fact is, the insignificant man with the splendid wife was a very mysterious personage, and it is the habit of the police to imagine that mystery always hides either the conspirator, the adventurer, or the charlatan. The conclusion to which the Prefect had 152 come in regard to M. de Lassa was that he was an adventurer and charlatan too. Certainly a successful one, then, for he was singularly unobtrusive and had in no way trumpeted the wonders which it was his mission to perform, yet in a few weeks after he had established himself in Paris the salon of M. de Lassa was the rage, and the number of persons who paid the fee of 100 francs for a single peep into his magic crystal, and a single message by his spiritual telegraph, was really astonishing. The secret of this was that M. de Lassa was a conjurer and diviner, whose pretensions were omniscient and whose predictions always came true.

Delessert did not find it very difficult to get an introduction and admission to de Lassa’s salon. The receptions occurred every other day—two hours in the forenoon, three hours in the evening. It was evening when Inspector Delessert called in his assumed character of M. Flabry, virtuoso in jewels and a convert to Spiritualism. He found the handsome parlors brilliantly lighted, and a charming assemblage gathered of well-pleased guests, who did not at all seem to have come to learn their fortunes or fates, while contributing to the income of their host, but rather to be there out of complaisance to his virtues and gifts.

Mme. de Lassa performed upon the piano or conversed from group to group in a way that seemed to be delightful, while M. de Lassa walked about or sat in his insignificant, unconcerned way, saying a word now and then, but seeming to shun everything that was conspicuous. Servants handed about refreshments, ices, cordials, wines, etc., and Delessert could have fancied himself [to have] dropped in upon a quite modest evening entertainment, altogether en règle, but for one or two noticeable circumstances which his observant eyes quickly took in.

Except when their host or hostess was within hearing, the guests conversed together in low tones, rather mysteriously, and with not quite so much laughter as is usual on such occasions. At intervals a very tall and dignified footman would come to a guest, and, with a profound bow, present him a card on a silver salver. The guest would 153then go out, preceded by the solemn servant, but when he or she returned to the salon—some did not return at all—they invariably wore a dazed or puzzled look, were confused, astonished, frightened, or amused. All this was so unmistakably genuine, and de Lassa and his wife seemed so unconcerned amidst it all, not to say distinct from it all, that Delessert could not avoid being forcibly struck and considerably puzzled.

Two or three little incidents, which came under Delessert’s own immediate observation, will suffice to make plain the character of the impressions made upon those present. A couple of gentlemen, both young, both of good social condition, and evidently very intimate friends, were conversing together and tutoying one another at a great rate, when the dignified footman summoned Alphonse. He laughed gaily. “Tarry a moment, cher Auguste,” said he, “and thou shalt know all the particulars of this wonderful fortune!” “Eh bien!” responded Auguste, “may the oracle’s mood be propitious!” A minute had scarcely elapsed when Alphonse returned to the salon. His face was white and bore an appearance of concentrated rage that was frightful to witness. He came straight to Auguste, his eyes flashing, and bending his face toward his friend, who changed colour and recoiled, he hissed out, “Monsieur Lefébure, vous êtes un lâche!” “Very well, Monsieur Meunier,” responded Auguste, in the same low tone, “to-morrow morning at six o’clock!” “It is settled, false friend, execrable traitor! À la mort!” rejoined Alphonse, walking off. “Cela va sans dire!” muttered Auguste, going towards the hat-room.

A diplomatist of distinction, representative at Paris of a neighboring state, an elderly gentleman of superb aplomb and most commanding appearance, was summoned to the oracle by the bowing footman. After being absent about five minutes he returned, and immediately made his way through the press to M. de Lassa, who was standing not far from the fireplace, with his hands in his pockets, and a look of utmost indifference upon his face. Delessert standing near, watched the interview with eager interest. “I am 154exceedingly sorry,” said General Von—,“to have to absent myself so soon from your interesting salon, M. de Lassa, but the result of my séance convinces me that my dispatches have been tampered with.” “I am sorry,” responded M. de Lassa, with an air of languid but courteous interest, “I hope you may be able to discover which of your servants has been unfaithful.” “I am going to do that now,” said the General, adding, in significant tones, “I shall see that both he and his accomplices do not escape severe punishment.” “That is the only course to pursue, Monsieur le Comte.” The ambassador stared, bowed, and took his leave with a bewilderment on his face that was beyond the power of his tact to control.

In the course of the evening M. de Lassa went carelessly to the piano, and, after some indifferent vague preluding, played a remarkably effective piece of music, in which the turbulent life and buoyancy of bacchanalian strains melted gently, almost imperceptibly away, into a sobbing wail of regret and languor, and weariness and despair. It was beautifully rendered, and made a great impression upon the guests, one of whom, a lady, cried, “How lovely, how sad! Did you compose that yourself, M. de Lassa?” He looked towards her absently for an instant, then replied: “I? Oh, no! That is merely a reminiscence, madame.” “Do you know who did compose it, M. de Lassa?” enquired a virtuoso present. “I believe it was originally written by Ptolemy Auletes, the father of Cleopatra,” said M. de Lassa, in his indifferent, musing way, “but not in its present form. It has been twice re-written to my knowledge; still, the air is substantially the same.” “From whom did you get it, M. de Lassa, if I may ask?” persisted the gentleman. “Certainly! certainly! The last time I heard it played was by Sebastian Bach; but that was Palestrina’s—the present—version. I think I prefer that of Guido of Arezzo—it is ruder, but has more force. I got the air from Guido himself.” “You—from—Guido!” cried the astonished gentleman, “Yes, monsieur,” answered de Lassa, rising from the piano with his usual indifferent air. “Mon Dieu!” cried the virtuoso, putting his hand to his head after the manner of 155Mr. Twemlow, “Mon Dieu! that was in Anno Domini 1022!” “A little later than that—July 1031, if I remember rightly,” courteously corrected M. de Lassa.

At this moment the tall footman bowed before M. Delessert, and presented the salver containing the card. Delessert took it and read: “On vous accorde trente-cinq secondes, M. Flabry, tout au plus!” Delessert followed the footman from the salon across the corridor. The footman opened the door of another room and bowed again, signifying that Delessert was to enter. “Ask no questions,” he said briefly; “Sidi is mute.” Delessert entered the room and the door closed behind him. It was a small room, with a strong smell of frankincense pervading it. The walls were covered completely with red hangings that concealed the windows, and the floor was felted with a thick carpet. Opposite the door, at the upper end of the room near the ceiling, was the face of a large clock; under it, each lighted by tall wax candles, were two small tables containing, the one an apparatus very like the common registering telegraph instrument, the other a crystal globe about twenty inches in diameter, set upon an exquisitely wrought tripod of gold and bronze intermingled. By the door stood Sidi, a man jet black in colour, wearing a white turban and burnous, and having a sort of wand of silver in one hand. With the other, he took Delessert by the right arm above the elbow, and led him quickly up the room. He pointed to the clock, and it struck an alarm; he pointed to the crystal. Delessert bent over, looked into it and saw—a facsimile of his own sleeping-room, everything photographed exactly. Sidi did not give him time to exclaim, but still holding him by the arm, took him to the other table. The telegraph-like instrument began to click-click. Sidi opened the drawer, drew out a slip of paper, crammed it into Delessert’s hand, and pointed to the clock, which struck again. The thirty-five seconds were expired. Sidi, still retaining hold of Delessert’s arm, pointed to the door and led him towards it. The door opened, Sidi pushed him out, the door closed, the tall footman stood there bowing, the interview with the oracle was over. Delessert glanced at 156the piece of paper in his hand. It was a printed scrap, capital letters, and read simply: “To M. Paul Delessert: The policeman is always welcome; the spy is always in danger!

Delessert was dumbfounded a moment to find his disguise detected; but the words of the tall footman, “This way, if you please, M. Flabry,” brought him to his senses. Setting his lips, he returned to the salon, and without delay sought M. de Lassa. “Do you know the contents of this?” asked he, showing the message. “I know everything, M. Delessert,” answered de Lassa, in his careless way. “Then perhaps you are aware that I mean to expose a charlatan, and unmask a hypocrite, or perish in the attempt?” said Delessert. “Cela m’est égal, monsieur,” replied de Lassa. “You accept my challenge, then?” “Oh! it is a defiance, then?” replied de Lassa, letting his eye rest a moment upon Delessert, “mais oui, je l’accepte!” And thereupon Delessert departed.

Delessert now set to work, aided by all the forces the Prefect of Police could bring to bear, to detect and expose this consummate sorcerer, whom the ruder processes of our ancestors would easily have disposed of—by combustion. Persistent enquiry satisfied Delessert that the man was neither a Hungarian nor named de Lassa; that no matter how far back his power of “reminiscence” might extend, in his present and immediate form he had been born in this unregenerate world in the toy-making city of Nuremberg; that he was noted in boyhood for his great turn for ingenious manufactures, but was very wild, and a mauvais sujet. In his sixteenth year he had escaped to Geneva and apprenticed himself to a maker of watches and instruments. Here he had been seen by the celebrated Robert Houdin, the prestidigitateur. Houdin, recognizing the lad’s talents, and being himself a maker of ingenious automata, had taken him off to Paris and employed him in his own workshops, as well as an assistant in the public performances of his amusing and curious diablerie. After staying with Houdin some years, Pflock Haslich (which was de Lassa’s right name) had gone East in the suite of a Turkish Pasha, 157and after many years’ roving, in lands where he could not be traced under a cloud of pseudonyms, had finally turned up in Venice, and come thence to Paris.

Delessert next turned his attention to Mme. de Lassa. It was more difficult to get a clue by means of which to know her past life; but it was necessary in order to understand enough about Haslich. At last, through an accident, it became probable that Mme. Aimée was identical with a certain Mme. Schlaff, who had been rather conspicuous among the demi-monde of Buda. Delessert posted off to that ancient city, and thence went into the wilds of Transylvania to Medgyes. On his return, as soon as he reached the telegraph and civilization, he telegraphed the Prefect from Karcag: “Don’t lose sight of my man, nor let him leave Paris. I will run him in for you two days after I get back.”

It happened that on the day of Delessert’s return to Paris the Prefect was absent, being with the Emperor at Cherbourg. He came back on the fourth day, just twenty-four hours after the announcement of Delessert’s death. That happened, as near as could be gathered, in this wise: the night after Delessert’s return he was present at de Lassa’s salon with a ticket of admittance to a séance. He was very completely disguised as a decrepit old man, and fancied that it was impossible for any one to detect him. Nevertheless, when he was taken into the room, and looked into the crystal, he was actually horror-stricken to see there a picture of himself, lying face down and senseless upon the side-walk of a street; and the message he received read thus: “What you have seen will be Delessert, in three days. Prepare!” The detective, unspeakably shocked, retired from the house at once, and sought his own lodgings.

In the morning he came to the office in a state of extreme dejection. He was completely unnerved. In relating to a brother inspector what had occurred, he said: “That man can do what he promises, I am doomed!”

He said that he thought he could make a complete case out against Haslich alias de Lassa, but could not do so w without seeing the Prefect, and getting instructions. He would 158tell nothing in regard to his discoveries in Buda and in Transylvania—said that he was not at liberty to do so—and repeatedly exclaimed: “Oh! if M. le Préfet were only here!” He was told to go to the Prefect at Cherbourg, but refused, upon the ground that his presence was needed in Paris. He time and again averred his conviction that he was a doomed man, and showed himself both vacillating and irresolute in his conduct, and extremely nervous. He was told that he was perfectly safe, since de Lassa and all his household were under constant surveillance; to which he replied; “You do not know the man.” An inspector was detailed to accompany Delessert, never lose sight of him night and day, and guard him carefully; and proper precautions were taken in regard to his food and drink, while the guards watching de Lassa were doubled.

On the morning of the third day, Delessert, who had been staying chiefly indoors, avowed his determination to go at once and telegraph to M. le Préfet to return immediately. With this intention he and his brother-officer started out. Just as they got to the corner of the Rue de Lancry and the Boulevard, Delessert stopped suddenly and put his hand to his forehead.

“My God!” he cried, “the crystal! the picture!” and he fell prone upon his face, insensible. He was taken at once to a hospital, but only lingered a few hours, never regaining his consciousness. Under express instructions from the authorities, a most careful, minute, and thorough autopsy was made of Delessert’s body by several distinguished surgeons, whose unanimous opinion was, that the cause of his death was apoplexy, due to fatigue and nervous excitement.

As soon as Delessert was sent to the hospital, his brother-inspector hurried to the Central Office, and de Lassa, together with his wife and every one connected with the establishment, were at once arrested. De Lassa smiled contemptuously as they took him away. “I knew you were coming; I prepared for it. You will be glad to release me again.”

It was quite true that de Lassa had prepared for them. 159When the house was searched, it was found that every paper had been burned, the crystal globe was destroyed, and in the room of the séances was a great heap of delicate machinery broken into indistinguishable bits. “That cost me 200,000 francs,” said de Lassa, pointing to the pile, “but it has been a good investment.” The walls and floors were ripped out in several places, and the damage to the property was considerable. In prison neither de Lassa nor his associates made any revelations. The notion that they had something to do with Delessert’s death was quickly dispelled, in a legal point of view, and all the party but de Lassa were released. He was still detained in prison, upon one pretext or another, when one morning he was found hanging by a silk sash to the cornice of the room where he was confined—dead. The night before, it was afterwards discovered, “Madame” de Lassa had eloped with a tall footman, taking the Nubian Sidi with them.

De Lassa’s secrets died with him.

[In the next issue of the Spiritual Scientist, namely, December 2, 1875, p. 151, the following Editorial Note was published:]

“It is an interesting story,—that article of yours in today’s Scientist. But is it a record of facts, or a tissue of the imagination? If true, why not state the source of it; in other words, specify your authority for it?”

The above is not signed, but we would take the opportunity to say, that the story, “An Unsolved Mystery,” was published because we considered the main points of the narrative,—the prophecies, and the singular death of the officer—to be psychic phenomena, that have been, and can be again produced. Why quote “authorities”? The Scriptures tell us of the death of Ananias, under the stern rebuke from Peter; here we have a phenomenon of a similar nature. Ananias is supposed to have suffered instant death from fear. Few can realize this power, governed by spiritual laws; but those who have trod the boundary line, and KNOW some few of the things that CAN be done, will see no great mystery in this, or the story published last week. We are not speaking in mystical tones. Ask the powerful mesmerist if there is danger that the subject may pass out from his control? If 160 he could will the spirit out, never to return? It is capable of demonstration, that the mesmerist can act on a subject at a distance of many miles; and it is no less certain that the majority of mesmerists know little or nothing of the laws that govern their powers.

It may be a pleasant dream to attempt to conceive of the beauties of the spirit-world; but the time can be spent more profitably in a study of the spirit itself, and it is not necessary that the subject for study should be in the spirit-world.

[In the same issue of the Spiritual Scientist, on page 147, there appeared the following letter to the Editor which throws further light upon this remarkable story:]

To the Editor of the Spiritual Scientist.

Sir:—

I am quite well aware of the source from whence originated the facts woven into the highly interesting story entitled “An Unsolved Mystery,” which appeared in No. 12, Vol. III, of your paper. I was myself at Paris at the time of the occurrences described, and personally witnessed the marvellous effects produced by the personage who figures in the anecdote as M. de Lasa. The attention you are giving to the subject of Occultism meets with the hearty approbation of all initiates—among which class it is idle for me to say whether I am or am not included.

You have opened to the American public a volume crammed, from cover to cover, with accounts of psychic phenomena surpassing in romantic interest the more wonderful experiences of the present day Spiritualism; and before long your paper will be quoted all over the world as their chief repository. Before long, too, the numerous writers in your contemporary journals, who have been gloating over the supposed discomfiture of your Russian friends, Mme. Blavatsky and the President of the Philosophical Académie, will have the laugh turned upon them, and wish they had not been so hasty in committing themselves to print. The same number which contains de Lassa’s story, has, in an article on “Occult Philosophy,” a suggestion that the supposed materialized spirit-forms, recently seen, may be only the simulacra of deceased people, resembling those individuals, but who are no more the real spirits than is the “photograph in your album” the sitter.

Among the notable personages I met in Paris at the time specified, was the venerable Count d’Ourches, then a hale, old gentleman nearly 161 ninety years of age. His noble parents perished on the scaffold in the Reign of Terror, and the events of that bloody epoch were stamped indelibly upon his memory. He had known Cagliostro and his wife, and had a portrait of that lady, whose beauty dazzled the courts of Europe. One day he hurried breathlessly into the apartment of a certain nobleman, residing on the Champs Élysées, holding this miniature in his hand and exclaiming, in great excitement: “Mon Dieu!—she has returned—it is she!—Madame Cagliostro is here!” I smiled at seeing the old Count’s excitement, knowing well what he was about to say. Upon quieting himself he told us he had just attended a séance of M. de Lasa, and had recognized in his wife the original of the miniature, which he exhibited, adding that it had come into his possession with other effects left by his martyred father. Some of the facts concerning the de Lasa are detailed very erroneously, but I shall not correct the errors.

I am aware that the first impulse of the facetious critics of Occultism will be to smile at my hardihood in endorsing, by implication, the possibility that the beautiful Madame de Lasa, of 1861, was none other than the equally beautiful Madame Cagliostro of 1786; at the further suggestion that it is not at all impossible that the proprietor of the crystal globe and clicking telegraph, which so upset the nerves of Delessert, the police spy, was the same person, who, under the name of Alessandro di Cagliostro, is reported by his lying biographers to have been found dead in the prison of Sant’ Angelo.

These same humorous scribblers will have additional provocation to merriment when I tell you that it is not only probable, but likely, that this same couple may be seen in this country before the end of the Centennial Exhibition, astounding alike professors, editors, and Spiritualists.

The initiates are as hard to catch as the sun-sparkle which flecks the dancing wave on a summer day. One generation of men may know them under one name in a certain country, and the nest, or a succeeding one, see them as someone else in a remote land.

They live in each place as long as they are needed and then—pass away “like a breath” leaving no trace behind.

ENDREINEK AGARDI, of Koloswar.

[In H.P.B.’s Scrapbook, Vol. I, p. 83, where the above Letter to the Editor of the Spiritual Scientist is pasted as a clipping, the author of it is identified as a pupil of Master M. The town formerly known as Kolozsvár was at that time within the boundaries of Hungary; it is now known as Cluj and is in the Transylvanian District of Rumania; its German equivalent was Klausenburg.

H.P.B. also says that the story, “An Unsolved Mystery” was written from the narrative of the Adept known as Hillarion, who sometimes signed himself Hillarion Smerdis, though the Greek original has only one “l” in it, as a rule. H.P.B. drops the initial 162 mark of an aspirate and uses merely the initial letter “I” as would be the case in Slavonic languages.

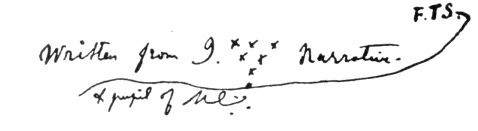

The facsimile of H.P.B.’s pen-and-ink notation in her Scrapbook is appended herewith.

The initiates are as hard to catch as the sun-sparkle which flecks the dancing wave on a summer day. One generation of man may know them under one name in a certain country, and the next, or a succeeding one, see them as some one else in a remote land.

They live in each place as long as they are needed and then—pass away “like a breath” leaving no trace behind.

ENDREINEK AGARDI, of Koloswar.

It is a curious fact that when Peter Davidson, F.T.S., published in The Theosophist (Vol. III, Feb. and March, 1882) an Old Tale about the Mysterious Brothers, which he transcribed from an eighteenth century work, he concluded his account with the following words:

“. . . . those mysterious ‘beings’ termed Brothers, Rosicrucians, etc., have been met with in every clime, from the crowded streets of ‘Civilized’ (!) London, to the silent crypts of crumbling temples in the ‘uncivilized’ desert; in short, wherever a mighty and beneficent purpose may call them or where genuine merit may attract them from their hermetic reticence, for one generation may recognize them by one name in a certain country, and the succeeding, or another generation meet them as someone else in a foreign land.” —Compiler.]

[Professor Hiram Corson of Ithaca, N.Y., in an article dated December 26, 1875, and published in the Banner of Light under the title of “The Theosophical Society and its President’s Inaugural Address,” sharply criticizes Col. Olcott’s Presidential Address of November 17, 1875, especially those portions of it which refer to Spiritualism. To the cutting of this article, as pasted in her Scrapbook, Vol. I, pp. 98-99, H.P.B. appended the following remarks:]

Oh, poor Yorick—we know him well! Aye even to having frequently seen him go to bed with his silk hat and dirty boots on. Hiram Yorick must have been drunk when he wrote this article.

See H. S. Olcott’s answer on page 112.