< The Psychological Influence of Material Objects Upon Sensitives (continued from page 7-188) >

see theory after theory thrown down as more and more light is revealed by the psychometric vision. I have known a psychometer to remain in the dark in reference to some important point after even five or six examinations; and where the objects examined are such that we cannot check the statements of the psychometer, or only by the statements of other psychometers, the greatest caution is necessary. For some examinations it is best that the psychometer should know nothing about the history desired from specimen; but, in most cases, the more highly cultured the psychometer is, the better and more reliable the results. Had Sherman the knowledge of comparative anatomy possessed by Owen of England, or of botany that Gray of America has, his description would be almost infinitely superior to what they are now, and carry conviction, by their harmony with known facts, to the minds of the most sceptical capable of appreciating them.

The parties experimenting need a good knowledge of the times to which the specimen is related, or they may think a psychometer very wide of the mark when his descriptions are the very truth. Many statements given in this volume I only discovered to be true after careful examinations of authorities; and many things stated, that I regarded at the time as extremely improbable, proved to be in complete harmony with known facts.

Psychometry will enable us to appreciate a class of people who have never yet had justice done to them. I refer to the sensitives, the “odd people” of the world, who see what no one else can discern; who dislike persons and places, though their friends may be perfectly satisfied with them, and can give no reason for their dislike. Some of them feel uncomfortable in a railway carriage unless close to an open window, and are liable to faint in churches or crowded halls. Some cannot sleep well unless their heads are to the north; and copper or brass affects them un- pleasantly. Such people are endowed by nature with a more active condition of the spiritual faculties; and they can, as a general thing, readily develop into good psycho- meters, who will, before long, fill a very prominent place in the intellectual advancement of the race. The lunatic asylum has imprisoned some of the best of these, in con- sequence of their extreme sensitiveness, who, by judicious treatment, might have been the noblest pioneers of science.

Woman, who is by nature much more sensitive than man, and who derives, often unwittingly, much knowledge by the exercise of her spiritual faculties, is to be greatly benefited by a knowledge of psychometry. Instead of spending her time in writing or reading caricatures of human nature, such as are nineteen-twentieths of our popular novels, she can read and write true histories of men and women, tracing the most noted characters of the past, rapidly or slowly, as she pleases, through every event of their lives, see and read the documents they have written, and hear the very words that fell from their lips, What fiction can equal such true stories as these? From experiments that I have tried, I am satisfied that many of them might go back from living individuals, step by step, into the past, along the line of either parent, and give a true description of their ancestors for thousands of years, Indeed, I know of no limit to this power.

The cultivation of the psychometric powers will aid materially, I think, in weakening the influence of the animal passions, and bringing the individual under the control of the moral and spiritual faculties. The passions may be gratified till the individual descends to the level of them, and the brute is master of the man; or the spiritual may be cultivated till it holds the reins, and guides the individual only where it is for his highest interest to travel. The habitual exercise of these highest powers allies us to the pure and good, and helps to bring about that better time for humanity that we all desire so much to see.

Psychometry will shed much light upon the spiritual nature of man. Every successful psychometric experiment is a revelation of its wondrous powers. I sometimes listen with breathless awe to the statements of psychometers as they unravel the profoundest mysteries of Nature; and I see that we possess powers which we have hitherto considered the exclusive property of the gods. If we could but realise what we are, we should scorn to be mean or impure. How could we, the royal children of Nature, live unworthy of our lineage and destiny?

Our destiny is also indicated by it. It cannot be that we should possess such powers as psychometry reveals, and yet these be scarcely used by one in a thousand. Death cannot extinguish these god-lit fires, which must bum and illumine for a future commensurate with the past that psychometry reveals. Here is a magnificent palace, on which architects have been employed for an immense period in rearing, improving, and decorating. Here are rooms fit for angels, and appliances innumerable for the comfort and happiness of those who may be fortunate enough to dwell in them. Is this built merely to be thrown down before one thousandth part of it has been occupied or used? These spiritual faculties that we possess are the evidences of the spiritual realm for which they are fitted, and where life is to be perpetuated under more favourable conditions. What the psychometer sees for an hour at a time, and with difficulty, we may be able to observe at leisure, and draw instruction from as a living volume. What a realm!—the heavens of all ages for the astronomer; all the past of our planet, and its myriad life-forms, for the geologist; all the facts of man’s existence for the historian; all plants, from the fucoids, that spread their arms on the tepid seas of the primeval world, to the soaring cedars of California, for the botanist; for the artist, all the giant mountains that the rains of aeons have washed away—the bare, black precipices, seamed with white veins, that frowned above the old Devonian seas; and the canons, eaten by the mad streams that went roaring through them, and then leaped into the ocean with a more than Niagara fall; the smoking mountains, the flaming craters, and the spouting geysers, not of this planet alone, but of all worlds in our system, and, it may be, of all worlds in all systems; the ever-growing soul finding unlimited time and an ever-expanding universe to gratify its unceasing desire to be, to do, and to learn.

Editor's notes

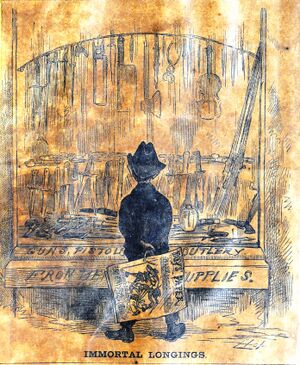

- ↑ Immortal Longings by unknown author