|

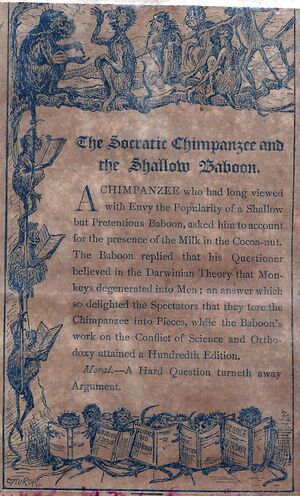

The Socratic Chimpanzee and the Shallow Baboon... |

Madame Blavatsky on the Vews of the Theosophists

Sir, – Permit an humble Theosophist to appear for the first time in your columns, to say a few words in defence of our beliefs. I see in your issue of December 21st ultimo, one of your correspondents, Mr. J. Croucher, makes the following very bold assertions: “Had the Theosophists thoroughly comprehended the nature of the soul and spirit, and its relation to the body, they would have known that if the soul once left the body, it could not return. The spirit can leave, but if the soul once leaves, it leaves for ever.” This is so ambiguous that, unless he uses the term “soul” to designate only the vital principle, I can only suppose that he falls into the common error of calling the astral body, spirit, and the immortal essence, “soul.” We, Theosophists, as Colonel Olcott has told you, do vice versa.

Besides the unwarranted imputation to us of ignorance, Mr. Croucher has an idea (peculiar to himself) that the problem which has heretofore taxed the powers of the metaphysicians in all ages has been solved in our own. It is hardly to be supposed that Theosophists or any others “thoroughly” comprehend the nature of the soul and spirit, and their relation to the body. Such an achievement is for Omniscience; and we Theosophists, treading the path worn by the footsteps of the old sages in the moving sands of exoteric philosophy, can only hope to approximate the absolute truth. It is really more than doubtful whether Mr. Croucher can do better, even though an “inspirational medium,” and experienced “through constant sittings with one of the best trance mediums” in your country. I may well leave to time and Spiritual philosophy to entirely vindicate us in the far hereafter. When any Oedipus of this or the next century shall have solved this eternal enigma of the Sphinx-man, every modern dogma, not excepting some pets of the Spiritualists, will be swept away, as the Theban monster, according to the legend, leaped from his promontory into the sea, and was seen no more.

As early as February 18th, 1876, your learned correspondent, “M. A. (Oxon.),” took occasion, in an article entitled “Soul and Spirit,” to point out the frequent confusion of the terms by other writers. As things are no better now, I will take the opportunity to show how sorely Mr. Croucher, and many other Spiritualists of whom he may be taken as the spokesman, misapprehended Colonel Olcott’s meaning, and the views of the New York Theosophists. Colonel Olcott neither affirmed nor dreamed of implying that the immortal spirit leaves the body to produce the medial displays. And yet Mr. Croucher evidently thinks he did, for the word “spirit” to him means the inner astral man or double. Here is what Colonel Olcott did say, double commas and all:

“2. That mediumistic physical phenomena are not produced by pure spirits, but by “souls” embodied or disembodied, and usually with the help of elementals.”

Any intelligent reader must perceive that, in placing the word “souls” in quotation marks, the writer indicated that he was using it in a sense not his own. As a Theosophist, he would more properly and philosophically have said for himself “astral spirits,” or “astral men,” or doubles. Hence, the criticism is wholly without even a foundation of plausibility. I wonder that a man could be found who, on so frail a basis, would have attempted so sweeping a denunciation. As it is, our President only propounded the trine of man, like the ancient and Oriental philosophers and their worthy imitator Paul, who held that the physical corporeity, the flesh and blood, was permeated and so kept alive by the psychê, the soul or astral body. This doctrine, that man is trine—spirit, or nous, soul and body—was taught by the Apostle of the Gentiles more broadly and clearly than it has been by any of his Christian successors (see 1 Thess., v, 23). But having evidently forgotten or neglected to “thoroughly” study the transcendental opinions of the ancient philosophers and the Christian Apostles upon the subject, Mr. Croucher views the soul–psychê as spirit–nous, and vice versa.

The Buddhists, who separate the three entities in man (though viewing them as one when on the path to Nirvana), yet divide the soul into several parts, and have names for each of these and their functions. Thus confusion is unknown among them. The old Greeks did likewise, holding that psychê was bios, or physical life, and it was thumos, or passional nature, the animals being accorded but a lower faculty of the soul-instinct. The soul or psychê is itself a combination, consensus or unity of the bios, or physical vitality, the epithumia or concupiscible nature, and the phren, mens, or mind. Perhaps the animus ought to be included. It is constituted of ethereal substance, which pervades the whole universe, and is derived wholly from the soul of the world—Anima Mundi or the Buddhist Svabhavat—which is not spirit; though intangible and impalpable, it is yet, by comparison with spirit or pure abstraction—objective matter. By its complex nature, the soul may descend and ally itself so closely to the corporeal nature as to exclude a higher life from exerting any moral influence upon it. On the other hand, it can so closely attach to the nous or spirit, as to share its potency, in which case its vehicle, physical man, will appear as a God even during his terrestrial life. Unless such union of soul and spirit does occur, either during this life or after physical death, the individual man is not immortal as an entity. The psychê is sooner or later disintegrated. Though the man may have gained “the whole world,” he has lost his “soul.” Paul, when teaching the anastasis, or continuation of individual spiritual life after death, set forth that there was a physical body which was raised in incorruptible substance. The spiritual body is most assuredly not one of the bodies, or visible or tangible larvae, which form in circle-rooms, and are so improperly termed “materialized spirits.” When once the metanoia, the full developing of spiritual life, has lifted the spiritual body out of the psychical (the disembodied, corruptible astral man, what Colonel Olcott calls “soul”), it becomes, in strict ratio with its progress, more and more an abstraction for the corporeal senses. It can influence, inspire, and even communicate with men subjectively; it can make itself felt, and even, in those rare instances, when the clairvoyant is perfectly pure and perfectly lucid, seen by the inner eye (which is the eye of the purified psychê—soul). But how can it ever manifest objectively?

It will be seen, then, that to apply the term “spirit” to the materialized eidola of your “form-manifestations,” is grossly improper, and something ought to be done to change the practice, since scholars have begun to discuss the subject. At best, when not what the Greeks termed phantasma, they are but phasma, or apparitions.

In scholars, speculators, and especially in our modern savants, the psychical principle is more or less pervaded by the corporeal, and “the things of the spirit are foolishness and impossible to be known” (1 Cor., ii, 14). Plato was then right, in his way, in despising land-measuring, geometry, and arithmetic, for all these overlooked all high ideas. Plutarch taught that at death Proserpine separated the body and the soul entirely, after which the latter became a free and independent demon (daïmon). Afterward, the good underwent a second dissolution: Demeter divided the psychê from the nous or pneuma. The former was dissolved after a time into ethereal particles hence the inevitable dissolution and subsequent annihilation of the man who at death is purely psychical; the latter, the nous, ascended to its higher Divine power and became gradually a pure, Divine spirit. Kapila, in common with all Eastern philosophers, despised the purely psychical nature. It is this agglomeration of the grosser particles of the soul, the mesmeric exhalations of human nature imbued with all its terrestrial desires and propensities, its vices, imperfections, and weakness, forming the astral body—which can become objective under certain circumstances which the Buddhists call skandhas (the groups), and Colonel Olcott has for convenience termed the “soul.” The Buddhists and Brahmanists teach that the man’s individuality is not secured until he has passed through and become disembarrassed of the last of these groups, the final vestige of earthly taint. Hence their doctrine of the metempsychosis, so ridiculed and so utterly misunderstood by our greatest Orientalists. Even the physicists teach us that the particles composing physical man are, by evolution, reworked by nature into every variety of inferior physical form. Why, then, are the Buddhists unphilosophical or even unscientific, in affirming that the semi-material skandhas of the astral man (his very ego, up to the point of final purification) are appropriated to the evolution of minor astral forms (which, of course, enter into the purely physical bodies of animals) as fast as he throws them off in his progress toward Nirvâna? Therefore, we may correctly say, that so long as the disembodied man is throwing off a single particle of these skandhas, a portion of him is being reincarnated in the bodies of plants and animals. And if he, the disembodied astral man, be so material that “Demeter” cannot find even one spark of the pneuma to carry up to the “divine power,” then the individual, so to speak, is dissolved, piece by piece, into the crucible of evolution, or, as the Hindus allegorically illustrate it, he passes thousands of years in the bodies of impure animals. Here we see how completely the ancient Greek and Hindu philosophers, the modern Oriental schools, and the Theosophists, are ranged on one side, in perfect accord; and the bright array of “inspirational mediums” and “spirit guides” stand in perfect discord on the other. Though no two of the latter, unfortunately, agree as to what is and what is not truth, yet they do agree with unanimity to antagonize whatever of the teachings of the philosophers we may repeat!

Let it not be inferred, though, from all this, that I, or any other real Theosophist, undervalue true Spiritual phenomena or philosophy, or that we do not believe in the communication between pure mortals and <... continues on page 4-199 >

Editor's notes

- ↑ image by unknown author

- ↑ The Socratic Chimpanzee and the Shallow Baboon by unknown author

- ↑ Madame Blavatsky on the Vews of the Theosophists by Blavatsky H.P., Spiritualist, The, London, February 8, 1878, pp. 68-69. Text copied from katinkahesselink.net and should be proofread against original newspaper text

This is pub. in "A Modern Panarion" .... – Archivist