Three things from H. P. Blavatsky's work room

At the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar (Chennai, India) there is a museum of the Theosophical movement. It contains a variety of things that belonged to prominent Theosophists, presented to them or having something to do with them.

One of the expositions of said museum is a stand with personal belongings from the work room of H.P. Blavatsky. Each of them deserves the special attention of Theosophists, like everything connected with her name. It is not because of our worshiping her personality and not because of a sentimental or formal tribute to one of the T.S. founders, but because of HPB’s unusual, multifaceted life, permeated with the idea of serving humanity and her Masters. This naturally leaves impressions on everything that surrounds such a person. Every detail of the life of such extraordinary people can arouse deep speculations, including ones of accidental and non-accidental appearance of some things in our own environment.

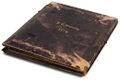

Diary

One of these belongings is a diary, which has an engravement in gold on the face side of the cover: “H. P. Blavatsky 1878 ". The diary has no records, only a small mark in blue ink in the upper left corner, where the number 7 is clearly visible. There is elso a short note inside: "Sarah Cowell F.T.O presents this album to HP Blavatsky 1878". Above this inscription, a note of the archival worker was made in blue ink: "Box 13.36". Apparently this is the place where this exhibit is kept.

As you can see in the pictures, the diary is rather shabby. Who knows, it may have once contained many pages that were used for notes and letters. The remaining cover and a few pages are damaged by worms, but the paper is not very yellow.

The notebook has dimensions of 240x200 mm.

A small tray

The next item is a small metal tray measuring 125x113 mm.

The tray is gracefully decorated: raging waves, soaring birds and a dragon framing this picture.

Perhaps the tray was used for a hot mug, and judging by the dark spots, it could well be used sometimes as an ashtray.

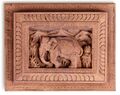

Wood-engraved picture

Another exhibit of the museum is a three-dimensional artwork, engraved in a whole piece of wood in the intaglio method, measuring 94x75 mm. It shows a walking elephant with mountains and some trees in the background. The material is unknown, but judging by the fringed edges of the engraving, it looks like some kind of soft wood.

These and other exhibits came to the museum after the death of H.P. Blavatsky, as they were found in her work room. Perhaps someday it will be possible to learn the history of at least some of them. It is not known how long Helena Petrovna had them in her work room, and whether they were presented to her personally or intended for someone else, whether she carried any of this things with her, or whether these items gradually appeared in her room along with numerous visitors. Only her diary contains fairly definite evidence of their owner, date and purpose.

As you know, Helena Petrovna was not attached to things and easily left any environment when her life's work called to move on. And she traveled a lot, one might say constantly. The reason for having most of her belongings (though not so many) was not the things themselves, but the people associated with them; as it is said about the portraits of her friends and acquaintances with which she decorated her work room in London (See the article “HPB at Work” in the previous sixth issue of MMT).

What thoughts can arise when looking at these things, which were once in demand and used and became antiquarian overnight, as soon as their mistress (or keeper) left this world?

Do we need all the things we have? Does everything really belong to us? Why do we have them? Maybe some of them are really needed for current usage, some – for future needs, and the other part (perhaps the largest) is just a test for our attachment to things as such. In the latter case, the idea that each person is a manifestation of the One Life, in which all processes are interconnected, can help, and therefore, we are often the vehicles of some more extensive processes that do not end with us, but only include us as participants. In other words, some of the things that come to us are intended for someone else, and we are only temporary custodians. We are trusted to convey something to others, but due to weak eyesight, we do not see the addressee and believe that since the thing has come to us, then it belongs to us.

With this thought, we can reconsider our belongings and fulfill our duty as an intermediary – to transfer things to someone who really needs them.