284...

CLASSIFICATION OF “PRINCIPLES”

[The Theosophist, Vol. VIII, No. 91, April, 1887, pp. 448-456]

In a most admirable lecture by Mr. T. Subba Row on the Bhagavad Gita, published in the February number of The Theosophist,[1] the lecturer deals, incidentally as 285I believe, with the question of septenary “principles” in the Kosmos and Man. The division is rather criticized, and the grouping hitherto adopted and favoured in theosophical teachings is resolved into one of Four.

This criticism has already given rise to some misunderstanding, and it is argued by some that a slur is thrown on the original teachings. This apparent disagreement with one whose views are rightly held as almost decisive on occult matters in our Society is certainly a dangerous handle to give to opponents who are ever on the alert to detect and blazon forth contradictions and inconsistencies in our philosophy. Hence I feel it my duty to show that there is in reality no inconsistency between Mr. Subba Row’s views and our own in the question of the septenary division; and to show, (a) that the lecturer was perfectly well acquainted with the septenary division before he joined the Theosophical Society; (b) that he knew it was the teaching of old Aryan “philosophers [who] have associated seven occult powers with the seven principles” in the Macrocosm and the Microcosm (see the end of this article); and (c) that from the beginning he had objected—not to the classification but to the form in which it was expressed. Therefore, now, when he calls the division “unscientific and misleading,” and adds that “this sevenfold classification is almost conspicuous by its absence in many [not all?] of our Hindu books,” etc., and that it is better to adopt the time-honoured classification of four principles, Mr. Subba Row must mean only some special orthodox books, as it would be impossible for him to contradict himself in such a conspicuous way.

A few words of explanation, therefore, will not be altogether out of place. For the matter of being “conspicuous by its absence” in Hindu books, the said classification is as conspicuous by its absence in Buddhist books. This, for a reason transparently clear: it was always esoteric; and as such, rather inferred than openly taught. That it is “misleading” is also perfectly true; for the great feature of the day—materialism—has led the minds of our Western theosophists into the 286prevalent habit of viewing the seven principles as distinct and self existing entities, instead of what they are—namely, upadhis and correlating states—three upadhis, basic groups, and four principles. As to being “unscientific,” the term can be only attributed to a lapsus linguae, and in this relation let me quote what Mr. Subba Row wrote about a year before he joined the Theosophical Society in one of his ablest articles, “Brahmanism on the Sevenfold Principle in Man,” the best review that ever appeared of the “Fragments of Occult Truth”—since embodied in Esoteric Buddhism. Says the author:—

I have carefully examined it [the teaching], and find that the results arrived at (in the Buddhist doctrine) do not seem to differ much from the conclusions of our Aryan philosophy, though our mode of stating the arguments may differ in form.

Having enumerated after this the “three primary causes” which bring the human being into existence—i.e., Parabrahman, Śakti and Prakriti—he explains:

As a general rule, whenever seven entities are mentioned in the ancient occult sciences of India, in any connection whatsoever, you must suppose that those seven entities came into existence from three primary entities; and that these three entities again are evolved out of a single entity or Monad. (See Five Years of Theosophy, p. 160.)

287 This is quite correct, from the occult standpoint, and also kabbalistically, when one looks into the question of the seven and ten Sephiroths, and the seven and ten Rishis, Manus, etc. It shows that in sober truth there is not nor can there be any fundamental disagreement between the esoteric philosophy of the Trans- and Cis-Himalayan Adepts. The reader is referred, moreover, to the earlier pages of the above-mentioned article, in which it is stated that

. . . . . the knowledge of the occult powers of nature possessed by the inhabitants of the lost Atlantis was learnt by the ancient adepts of India and was appended by them to the esoteric doctrine taught by the residents of the sacred Island [now the Gobi desert][3]. The Tibetan adepts, however [their precursors of Central Asia], have not accepted this addition. . . . . (pp. 155-56).

But this difference between the two doctrines does not include the septenary division, as it was universal after it had originated with the Atlanteans, who, as the Fourth Race, were of course an earlier race than the Fifth—the Aryan.

Thus, from the purely metaphysical standpoint, the remarks made on the Septenary Division in the “Bhagavad-Gita” Lecture hold good to-day, as they did five or six years ago in the article “Brahmanism on the Sevenfold Principle in Man,” their apparent discrepancy notwithstanding. For purposes of purely theoretical esotericism, they are as valid in Buddhist as they are in Brahmanical philosophy. Therefore, when Mr. Subba Row proposes to hold to “the time-honoured classification of four principles” in a lecture on a Vedanta work—the Vedantic classification, however, dividing man into “five kosas” (sheaths) and the Atma (the six nominally of course),[4] he simply shows thereby that he desires to remain strictly within theoretical and metaphysical, and 288also orthodox computations of the same. This is how I understand his words, at any rate. For the Taraka Raja-Yoga classification is again three upadhis, the Atma being the fourth principle, and no upadhi, of course, as it is one with Parabrahm. This is again shown by himself in a little article called “Septenary Division in Different Indian Systems.” [5]

Why then should not “Buddhist” Esotericism, so-called, resort to such a division? It is perhaps “misleading”—that is admitted; but surely it cannot be called “unscientific.” I will even permit myself to call that adjective a thoughtless expression, since it has been shown to be on the contrary very “scientific” by Mr. Subba Row himself; and quite mathematically so, as the afore-quoted algebraic demonstration of the same proves it. I say that the division is due to nature herself pointing out its necessity in kosmos and man; just because the number seven is “a power, and a spiritual force” in its combination of three and four, of the triangle and the quaternary. It is no doubt far more convenient to adhere to the fourfold classification in a metaphysical and synthetical sense, just as I have adhered to the threefold classification—of body, soul and spirit—in Isis Unveiled, because had I then adopted the septenary division, as I have been compelled to do later on for purposes of strict analysis, no one would have understood it, and the multiplication of principles, instead of throwing light upon the subject, would have introduced endless confusion. But now the question has changed, and the position is different. We have unfortunately—for it was premature—opened a chink in the Chinese wall of esotericism, and we cannot now close it again, even if we would. I for one had to pay a heavy price for the indiscretion, but I will not shrink from the results.

I maintain then, that when once we pass from the plane of pure subjective reasoning on esoteric matters to that of practical demonstration in Occultism, wherein 289each principle and attribute has to be analysed and defined in its application to the phenomena of daily and especially of post-mortem life, the sevenfold classification is the right one. For it is simply a convenient division which prevents in no wise the recognition of but three groups—which Mr. Subba Row calls “four principles associated with four upadhis, which are further associated in their turn with four distinct states of consciousness.”[6] This is the Bhagavad-Gita classification, it appears; but not that of the Vedanta, nor—what the Raja-Yogis of the pre-Aryasangha schools and of the Mahayana system held to, and still hold beyond the Himalayas, and their system is almost identical with the Taraka Raja-Yoga—the difference between the latter and the Vedanta classification having been pointed out to us by Mr. Subba Row in his little article on the “Septenary Division in Different Indian Systems.” The Taraka Raja-Yogis recognize only three upadhis in which Atma may work, which, in India, if I mistake not, are the Jagrata, or waking state of consciousness (corresponding to the Sthulopadhi); the Svapna, or dreaming state (in Sukshmopadhi), and the Sushupti, or causal state, produced by, and through Karanopadhi, or what we call Buddhi. But then, in transcendental states of Samadhi, the body with its linga sarira, the vehicle of the life-principle, is entirely left out of consideration: the three states of consciousness are made to refer only to the three (with Atma the fourth) 290principles which remain after death. And here lies the real key to the septenary division of man, the three principles coming in as an addition only during his life.

As in the Macrocosm, so in the Microcosm; analogies hold good throughout nature. Thus the universe, our solar system, our earth down to man, are to be regarded as all equally possessing a septenary constitution—four superterrestrial and superhuman, so to say; three objective and astral. In dealing with the special case of man, only, there are two standpoints from which the question may be considered. Man in incarnation is certainly made up of seven principles, if we so term the seven states of his material, astral, and spiritual framework, which are all on different planes. But if we classify the principles according to the seat of the four degrees of consciousness, these upadhis may be reduced to four groups.[7] Thus his consciousness, never being centred in the second or third principles—both of which are composed of states of matter (or rather of “substance”) on different planes, each corresponding to one of the planes and principles in Kosmos—is necessary to form links between the first, fourth, and fifth principles, as well as subserving certain vital and psychic phenomena. These latter may be conveniently classified with the physical body under one head, and laid aside during trance (Samadhi), as after death, thus leaving only the traditional exoteric and metaphysical four. Any charge of contradictory teaching, therefore, based on this simple fact, would obviously be wholly invalid; the classification. of principles as septenary or quaternary depending 291wholly on the standpoint from which they are regarded, as said. It is purely a matter of choice which classification we adopt. Strictly speaking, however, occult—as also profane—physics would favour the septenary one for these reasons.[8]

There are six Forces in Nature: this in Buddhism as in Brahmanism, whether exoteric or esoteric, and the seventh—the all-Force, or the absolute Force, which is the synthesis of all. Nature again in her constructive activity strikes the key-note to this classification in more than one way. As stated in the third aphorism of Sankhya-karika of Prakriti—“the root and substance of all things,” she (Prakriti, or nature) is no production, but herself a producer of seven things, “which, produced by her, become all in their turn producers.” Thus all the liquids in nature begin, when separated from their parent mass, by becoming a spheroid (a drop); and when the globule is formed, and it falls, the impulse given to it transforms it, when it touches ground, almost invariably into an equilateral triangle (or three), and then into an hexagon, after which out of the corners of the latter begin to be formed squares or cubes as plane figures. Look at the natural work of nature, so to speak, her artificial, or helped production—the prying into her occult workshop by science. Behold the coloured rings of a soap-bubble, and those produced by 292polarized light. The rings obtained, whether in Newton’s soap-bubble, or in the crystal through the polarizer, will exhibit invariably six or seven rings—a black spot surrounded by six rings, or a circle with a plane cube inside, circumscribed with six distinct rings, the circle itself the seventh. The “Norremberg” polarizing apparatus throws into objectivity almost all our occult geometrical symbols, though physicists are none the wiser for it. (See Newton’s and Tyndall’s experiments.)[9]

The number seven is at the very root of occult Cosmogony and Anthropogony. No symbol to express evolution from its starting to its completion points would be possible without it. For the circle produces the point; the point expands into a triangle, returning after two angles upon itself, and then forms the mystical Tetraktis—the plane cube; which three when passing into the manifested world of effects, differentiated nature, become geometrically and numerically 3 + 4 = 7. The best kabbalists have been demonstrating this for ages ever since Pythagoras, and down to the modern mathematicians and symbologists, one of whom has succeeded in wrenching forever one of the seven occult keys, and has proven his victory by a volume of figures. Set any of our theosophists interested in the question to read the wonderful work called Key to the Hebrew-Egyptian Mystery in the Source of Measures;[10] and those of them who are good mathematicians will remain aghast before the revelations contained in it. For it shows indeed that occult source of the measure by which were built kosmos and man, and then by the latter the great Pyramid of Egypt, as all the towers, mounds, obelisks, cave-temples of` India, and pyramids in Peru and Mexico, and all the archaic monuments; symbols in stone of Chaldea, both Americas, and even of the Easter Island 293—the living and solitary witness of a submerged prehistoric continent in the midst of the Pacific Ocean. It shows that the same figures and measures for the same esoteric symbology existed throughout the world; it shows in the words of the author that the kabbala is a “whole series of developments based upon the use of geometrical elements; giving expression in numerical values, founded on integral values of the circle” (one of the seven keys hitherto known but to the Initiates), discovered by Peter Metius[11] in the 16th century, and re-discovered by the late John A. Parker.[12] Moreover, that the system from whence all these developments were derived “was anciently considered to be one resting in nature (or God), as the basis or law of the exertions practically of creative design”; and that it also underlies the Biblical structures, being found in the measurements given for Solomon’s temple, the ark of the Covenant, Noah’s Ark, etc., etc.,—in all the symbolical myths, in short, of the Bible.

And what are the figures, the measure in which the sacred Cubit is derived from the esoteric Quadrature, which the Initiates know to have been contained in the Tetraktis of Pythagoras? Why, it is the universal primordial symbol. The figures found in the Ansated Cross of Egypt, as (I maintain) in the Indian Swastika, “the sacred sign” which embellishes the thousand heads of Śesha, the Serpent-cycle of eternity, on which rests Vishnu, the deity in Infinitude; and which also may be pointed out in the threefold (treta) fire of Puraravas, the first fire in the present Manvantara, out of the forty-nine (7 x 7) mystic fires. It may be absent from many of the Hindu books, but the Vishnu and other Puranas teem with this symbol and figure under every possible form, which I mean to prove in the Secret Doctrine The author of the Source of Measures 294does not, of course, himself know as yet, the whole scope of what he has discovered. He applies his key, so far, only to the esoteric language and the symbology in the Bible, and the Books of Moses especially. The great error of the able author, in my opinion, is, that he applies the key discovered by him chiefly to post-Atlantean and quasi-historical phallic elements in the world religions; feeling, intuitionally, a nobler, a higher, a more transcendental meaning in all this—only in the Bible—and a mere sexual worship in all other religions. This phallic element, however, in the older pagan worship related, in truth, to the physiological evolution of the human races, something that could not be discovered in the Bible, as it is absent from it (the Pentateuch being the latest of all the old Scriptures). Nevertheless, what the learned author has discovered and proved mathematically, is wonderful enough, and sufficient to make our claim good: namely, that the figures and ⵔ △ □ 3+4= 7, are at the very basis, and are the soul of cosmogony and the evolution of mankind.

To whosoever desires to display this process by way of ☥ symbol, says the author speaking of the ansated cross, the Tau of the Egyptians and the Christian cross—

. . . . . it would be by the figure of the cube unfolded, in connection with the circle, whose measure is taken off onto the edges of the cube. (The cube unfolded becomes, in superficial display, a cross proper, or of the tau form, and the attachment of the circle to this last gives the ansated cross of the Egyptians, with its obvious meaning of the origin of measures.)[13] Because, also, this kind of measure was made to coordinate with the idea of the origin of human life, it was secondarily made to assume the type of the pudenda hermaphrodite, and, in fact, 295it is placed by representation to cover this part of the human person in the Hindu form.

It is “the hermaphrodite Indranse Indra, the nature goddess, the Issa of the Hebrews, and the Isis of the Egyptians,” as the author calls them in another place.

It is very observable that, while there are but 6 faces to a cube, the representation of the cross as the cube unfolded as to the cross-bars, displays one face of the cube as common to two bars, counted as belonging to either; then, while the faces originally represented are but 6, the use of the two bars counts the square as 4 for the upright and 3 for the cross-bar, making 7 in all. Here we have the famous 4, 3 and 7. The four and three are the factor members of the Parker [quadrature and of the “three revolving bodies”] problem. . . . . (pp. 50-51).

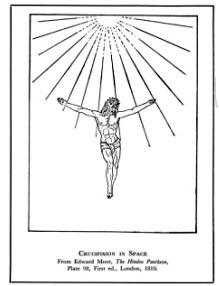

And they are the factor members in the building of the Universe and Man. Wittoba—an aspect of Krishna and Vishnu—is therefore the “man crucified in space,” or the “cube unfolded,” as explained (See Edward Moor’s The Hindoo Pantheon, for Wittoba).[14] It is the

296

297

oldest symbol in India, now nearly lost, as the real meaning of Viśvakarma and Vikartana (the “sun shorn of his beams”) is also lost. It is the Egyptian ansated cross, and vice versa, and the latter—even the sistrum, with its cross-bars—is simply the symbol of the Deity as man—however phallic it may have become later, after the submersion of Atlantis. The ansated cross is of course, as Professor Seyffarth has shown—again the six with its head—the seventh. Seyffarth says:

“It represents, as I now believe, the skull with the brains, the seat of the soul, and with the nerves extending to the spine, back, and eyes or ears. For the Tanis stone translates it repeatedly by anthropos (man), and this very word is alphabetically written (Egyptian) ank ☥. Hence we have the Coptic ank, vita, properly anima, which corresponds with the Hebrew אנוש, anosh, properly meaning anima. This אנוש is the primitive אנוך for אנכי (the personal pronoun I). The Egyptian Anki signifies my soul.”[15]

It means in its synthesis, the seven principles, the details coming later. Now the ansated cross, as given above, having been discovered on the backs of gigantic statues found on the Easter Island (mid-Pacific Ocean) which is a part of the submerged continent; this remnant being described as “thickly studded with cyclopean statues, remnants of the civilization of a dense and cultivated people”;—and Mr. Subba Row having told us what he 298had found in the old Hindu books, namely, that the ancient Adepts of India had learned occult powers from the Atlanteans (vide supra)—the logical inference is that they had their septenary division from them, just as our Adepts from the “Sacred Island” had. This ought to settle the question.

And this Tau cross is ever septenary, under whatever form—it has many forms, though the main idea is always one. What are the Egyptian oozas (the eyes) the amulets called the “mystic eye,” but symbols of the same? There are the four eyes in the upper row and the three smaller ones in the lower. Or again, the ooza with the seven luths hanging from it, “the combined melody of which creates one man,” say the hieroglyphics. Or again, the hexagon formed of six triangles, whose apices converge to a point, thus:

the symbol of the Universal creation, which Kenneth Mackenzie tells us “was worn as a ring by the Sovereign Princes of the Royal Secret”—which they never knew by the bye. If seven has nought to do with the mysteries of the universe and man, then indeed from Vedas down to the Bible all the archaic Scriptures—the Puranas, the Avesta and all the fragments that have reached us—have no esoteric meaning, and must be regarded as the Orientalists regard them—as a farago of childish tales.

It is quite true that the three upadhis of the Taraka Raja-Yoga are, as Mr. Subba Row explains in his little article, “Septenary Division in Different Indian Systems,” “the best and simplest”—but only in purely contemplative Yoga. And he adds:

. . . . . Though there are seven principles in man, there are but three distinct Upadhis (bases), in each of which his Atma may work independently of the rest. These three Upadhis can be separated by an adept without killing himself. He cannot separate the seven principles from each other without destroying his constitution.

299

Most decidedly he cannot. But this again holds good only with regard to his lower three principles—the body and its (in life) inseparable prana and linga sarira. The rest can be separated, as they constitute no vital, but rather a mental and spiritual necessity. As to the remark in the same article objecting to the fourth principle being “included in the third kośa (sheath), as the said principle is but the vehicle of will-power, which is but an energy of the mind,” I answer: Just so. But as the higher attributes of the fifth (Manas), go to make up the original triad, and it is just the terrestrial energies, feelings and volitions which remain in the Kama loka, what is the vehicle, the astral form to carry them about as bhoota until they fade out—which they take centuries to accomplish? Can the “false” personality, or the piśacha, whose ego is made up precisely of all those terrestrial passions and feelings, remain in Kamaloka, and occasionally appear, without a substantial vehicle, however ethereal? Or are we to give up the seven principles, and the belief that there is such a thing as an astral body, and a bhoot, or spook?

Most decidedly not. For Mr. Subba Row himself once more explains how, from the Hindu standpoint, the lower fifth, or Manas, can reappear after death, remarking very justly, that “it is absurd to call it a disembodied spirit.” As he says:

. . . . . It is merely a power or force retaining the impressions of the thoughts or ideas of the individual into whose composition it originally entered [italics H. P. B.’s]. It sometimes summons to its aid the Kâmarûpa power, and creates for itself some particular ethereal form (not necessarily human).

Now that which “sometimes summons” Kamarupa, and the “power” of that name make already two principles, two “powers”—call them as you will. Then we have Atma and its vehicle—Buddhi—which make four. With the three which disappeared on earth this will be equivalent to seven. How can we, then, speak of modern 300Spiritualism, of its materializations and other phenomena, without resorting to the Septenary?

To quote our friend and much respected brother for the last time, since he says that

. . . . our [Aryan] philosophers have associated seven occult powers with the seven principles [in men and in the kosmos] or entities above-mentioned. These seven occult powers in the microcosm correspond with, or are the counterparts of, the occult powers in the macrocosm. . . .*

—quite an esoteric sentence—it does seem almost a pity, that words pronounced in an extempore lecture, though such an able one, should have been published without revision.

Footnotes

- ↑ [This lecture is part of a series of lectures delivered by T. Subba Row under the general title of Notes on the Bhagavad Gîtâ. The introductory lecture of this series was given by him at the Anniversary Convention at Adyar, December, 1885, and was published in The Theosophist, Vol. VII, February, 1886, pp. 281-85. The four actual lectures—of which the one referred to and quoted from by H.P.B. in the present article is the First—were delivered a year later, namely, at the Anniversary Convention at Adyar, December 27-31, 1886. They appeared originally in The Theosophist, Vol. VIII, February, March, April and July, 1887. They were published later in book-form by Tookaram Tatya, Bombay, 1888, though some omissions occur in this edition. The best edition of this entire Series is the one published by Theosophical University Press, Point Loma, California, 1934, which incorporates corrections in the text which T. Subba Row himself considered necessary at the time (see The Theosophist, Vol. VIII, May, 1887, p. 511).—Compiler.]

- ↑ [The important essay of T. Subba Row quoted from by H.P.B. was originally published in The Theosophist, Vol. III, January, 1882, pp. 93-99, with additional notes and footnotes by H.P.B. herself. The title of this essay was: “The Aryan-Arhat Esoteric Tenets on the Sevenfold Principle in Man.” Five Years of Theosophy, as is well known, is mainly a collection of important articles and essays culled from the pages of The Theosophist. Subba Row’s essay with all the footnotes and Editorial Notes by H.P.B. will be found in Volume III of the present Series.—Compiler.]

- ↑ See Isis Unveiled, Vol. I, p. 600, and the appendices by the Editor [H.P.B.] to the above-quoted article in Five Years of Theosophy.

- ↑ This is the division given to us by Mr. Subba Row. See Five Years of Theosophy, pp. 185-86, article signed T.S.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 185-86.

- ↑ A crowning proof of the fact that the division is arbitrary and varies with the schools it belongs to, is in the words published in “Personal and Impersonal God “ by Mr. Subba Row, where he states that “. . . . we have six states of consciousness, either objective or subjective . . . . and a state of perfect unconsciousness. . . . . ” (See Five Years of Theosophy, pp. 200-201). Of course those who do not hold to the old school of Aryan and Arhat Adepts are in no way bound to adopt the septenary classification.

[Subba Row’s article mentioned above was published in The Theosophist, Vol. IV, February and March, 1883, pp. 104-05 and 183-89 respectively. The quotation in the text to which the above footnote is appended is from his “Notes on the Bhagavad-Gita,” The Theosophist, Vol. VIII, Feb., 1887, p. 301.—Compiler.] - ↑ Mr. Subba Row’s argument that in the matter of the three divisions of the body “we may make any number of divisions . . . . [and] may as well enumerate nerve-force, blood, and bones,” is not valid, I think. Nerve-force—well and good, though it is one with the life principle and proceeds from it; as to blood, bones, etc., these are objective material things, and one with, and inseparable from the human body; while all the other six principles are in their Seventh—the body—purely subjective principles, and therefore all denied by material science, which ignores them.

- ↑ In that most admirable article of his, “Personal and Impersonal God”—one which has attracted much attention in the Western Theosophical circles, Mr. Subba Row says, “Just as a human being is composed of seven principles, differentiated matter in the solar system exists in seven different conditions. These different states of matter do not all come within the range of our present objective consciousness. But they can be objectively perceived by the spiritual ego in man. . . . . Further, Prajña or the capacity of perception exists in seven different aspects corresponding to the seven conditions of matter. Strictly speaking, there are but six states of matter, the so-called seventh state being the aspect of Cosmic matter in its original undifferentiated condition. Similarly there are six states of differentiated Prajña, the seventh state being a condition of perfect unconsciousness. By differentiated Prajña, I mean the condition in which Prajña is split up into various states of consciousness. Thus we have six states of consciousness, etc., etc.” (Five Years of Theosophy, p. 200). This is precisely our Trans-Himalayan Doctrine.

- ↑ One need only open Webster’s Dictionary and examine the snow flakes and crystals at the word “Snow” to perceive nature’s work. “God geometrizes,” says Plato.

- ↑ [By J. Ralston Skinner. Cincinnati: R. Clarke & Co., 1875; 2nd ed., with Supplement, ibid., 1894; 3rd ed., Philadelphia: David McKay Co., 1931.]

- ↑ [Probably Adriaan A. Metius is meant here. Vide Bio-Bibliogr. Index under Metius.—Compiler.]

- ↑ Of Newark, in his work The Quadrature of the Circle, his “problem of the three revolving bodies” (New York: John Wiley and Son, 1851).

- ↑ And, by adding to the cross proper + the symbol of the four cardinal points and infinity at the same time, thus 卐, the arms pointing above, below, and right, and left, making six in the circle—the Archaic sign of the Yomas—it would make of it the Swastika, the “sacred sign” used by the order of “Ishmael masons,” which they call the Universal Hermetic Cross, and do not understand its real wisdom, nor know its origin. [H.P.B.]

- ↑ [The facsimile of the picture in E. Moor’s valuable work is reproduced herewith from its first edition (plate 98), published in London in 1810. The “New Edition,” edited by the Rev. W. O. Simpson, and published in 1864, fails to reproduce it, and the Reverend Editor says in a footnote (p. 283) that “this subject, a crucifix, is omitted in the present edition, for very obvious reasons,” leaving the reader to surmise what such “reasons” may have been. In speaking of the same picture elsewhere, H.P.B. refers the student to page 174 (fig. 72) of Dr. J. P. Lundy’s Monumental Christianity, where a facsimile of it can be found. Dr. Lundy says (p. 173): “I do not venture to give it a name, other than that of a crucifixion in space. It looks like a Christian crucifix in many respects, and in some others it does not. The drawing, the attitude, and the nail-marks in hands and feet, indicate a Christian origin; while the Parthian coronet of seven points, the absence of the wood and of the usual inscription, and the rays of glory above, would seem to point to some other than a Christian origin. Can it be the Victim-Man, or the Priest and Victim both in one, of the Hindu mythology, who offered himself a sacrifice before the worlds were? Can it be Plato’s second God who impressed himself on the universe in the form of the cross? Or is it his divine man who would be scourged, tormented, fettered, have his eyes burnt out; and lastly, having suffered all manner of evils, would be crucified? (Republic, c. ii, p. 52, Spens’ Trans.).”

Edward Moor wrote regarding this subject: “A man, who was in the habit of bringing me Hindu deities, pictures, etc., once brought me two images exactly alike: one of them is engraved in Plate 98, and the subject of it will be at once seen by the most transient glance. Affecting indifference, I inquired of the Pundit what Deva it was; he examined it attentively, and after turning it about for some time, returned it to me, professing his ignorance of what Avatara it could immediately relate to; but supposed, by the hole in the foot, that it might be Wittoba . . . .” Moor himself thought it to be of Christian origin, while Godfrey Higgins (Anacalypsis, I, pp. 145-146) considered it to be a genuine Wittoba.—Compiler.] - ↑ Quoted in Source of Measures, p. 53.

- ↑ Five Years of Theosophy, p. 186. [Also The Theosophist, Vol. V, p. 225.]

- ↑ Five Years of Theosophy, p. 174.