Pythagoras a Great Philosopher and Mystic

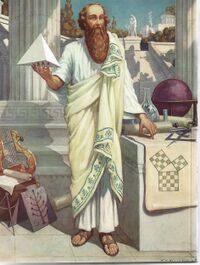

May I share with you a popular painting of Him with some symbolic objects. He holds in his right hand the tetrahedron symbolizing the 3-dimentional space and with his left hand he points to a drawing depicting the Pythagorean Theorem.

Pythagoras lived from around 570 to 490 B.C. He was an early Pre-Socratic philosopher and mathematician from the Greek island of Samos.

He was the founder of the influential philosophical and religious movement or cult called Pythagoreanism, and he was probably the first man to actually call himself a philosopher (or lover of wisdom). Pythagoras (or in a broader sense the Pythagoreans), allegedly exercised an important influence on the work of Plato.

As a mathematician, he is known as the "father of numbers" or as the first pure mathematician, and is best known for his Pythagorean Theorem on the relation between the sides of a right triangle, the concept of square numbers and square roots, and the discovery of the golden ratio.

None of the original writings of Pythagoras have survived, and his followers usually published their own works in his name. He remains something of a mysterious figure. His secret society or brotherhood had a great effect on later esoteric traditions such as Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry.

Pythagoras was born on the Greek island of Samos, in the eastern Aegean Sea, some time between 580 and 572 B.C. His father was Mnesarchus, a wealthy merchant, and his mother was Pythais, a native of Samos. He spent his early years in Samos, but also traveled widely with his father.

According to some reports, as a young man he met Thales, who was impressed with his abilities and advised him to head to Memphis in Egypt and study mathematics and astronomy with the priests there. He also travelled to study at the temples of Tyre and Byblos in Phoenicia, as well as in Babylon. At some point he was also a student of Pherecydes of Syros and of Anaximander (who himself had been a student of Thales).

Pythagoras stayed in Egypt 12 years during which he visited several temples, was accepted by the priests and he was given initiations in the Mysteries of Egypt. During his stay there Egypt was attacked by the Persians and according to some sources he was arrested and taken to Babylon, where he had contacts with the priests of Chaldea and certainly benefited from their wisdom.

He returned to his native Samos, which was going through a difficult period suffering the rule of a tyrant. Pythagoras was now about 40 years old and he wanted to share with his fellow Greeks the knowledge he had acquired in the east. In order to escape the tyrannical government of Polycrates, the Tyrant of Samos (or possibly to escape political problems related to an Egyptian-style school called the "semicircle" which he had founded on Samos) he left to mainland Greece.

Greece, under the Orphic influence had a spring of the arts, architecture, sculpturing, theater, etc.and majestic temples were erected in the Greek cities.

May I share the picture of the Parthenon.

He went to Delphi, where he stayed about a year. He was a magnetic speaker and the priests as well as the oracle happily listened to his interpretations of divine communications.

This was the 6th century BC and many Greek city – states had established colonies in southern Italy and Sicily. Wealthy cities had developed there and the Greek language and culture spread widely. The whole of southern Italy in this pre-roman period was called Magna Greacia, (Greater Greece).

Ionic was spoken in Samos and the Aegean islands. Ionic was related to the Attic dialect that was spoken in Athens. In the cities of Croton and Metapontium, in southern Italy, Doric was the spoken dialect, at the time of Pythagoras.

Pythagoras established in the city of Croton a secret religious society very similar to (and possibly influenced by) the earlier cult of Orpheus, in an attempt to reform the cultural life of Croton. He formed an elite circle of followers around himself, called Pythagoreans or the Mathematikoi ("learners"), subject to very strict rules of conduct, owning no personal possessions and assuming a largely vegetarian diet. They followed a structured life of religious teaching, common meals, exercise, music, poetry recitations, reading and philosophical study (very similar to later monastic life). The school (unusually for the time) was open to both male and female students uniformly (women were held to be different from men, but not necessarily inferior). The Mathematikoi extended and developed the more mathematical and scientific work Pythagoras began.

Students were accepted after a careful assessment that included some tests. During the first two years they were not allowed to talk or make questions. They had to go further tests and trials before they could continue in more advanced classes. They were known as the Akousmatikoi ("listeners"), and they focused on the more religious and ritualistic aspects of Pythagoras' teachings.

Some have wanted to relegate the more miraculous features of Pythagoras’ persona to the later tradition, but these characteristics figure prominently in the earliest evidence and are thus central to understanding Pythagoras. Aristotle emphasized his superhuman nature in the following ways: there was a story that Pythagoras had a golden thigh (a sign of divinity); the Pythagoreans taught that “of rational beings, one sort is divine, one is human, and another such as Pythagoras” (Iamblichus, the neoplatonic philosopher); Pythagoras was seen on the same day at the same time in both Metapontium and Croton; as he was crossing a river it spoke to him. According to Aristotle, the people of Croton called Pythagoras the “Hyperborean Apollo”.

According to Iamblichus a high priest from the land of the Hyperboreans, Avaris, visited Pythagoras and presented him with his arrow, a token of power. Some authors argue that the visit of Avaris is the key to understanding the identity and significance of Pythagoras. Avaris was a great mystic from Mongolia (part of what the Greeks called Hyperborea), who recognized Pythagoras as an incarnation of Apollo. The stillness of ecstasies practiced by Avaris and handed on to Pythagoras is the foundation of all civilization. Avaris’ visit to Pythagoras thus becomes the central moment when spiritual knowledge and power is passed from East to West.

Among his more prominent students were the philosopher Empedocles, Brontinus (who may have been Pythagoras' successor as head of the school), Philolaus, who has been credited with originating the theory that the earth was not the center of the universe, and others. One of the prominent students was Theano, a mathematician and possibly wife of Pythagoras.

Towards the end of his life, Pythagoras fled to Metapontium (further north in the Gulf of Tarantum) because of a plot against him and his followers by a noble of Croton named Cylon. He died in Metapontium from unknown causes some time between 500 and 490 B.C., between 80 and 90 years old.

Because of the secretive nature of his school and the custom of its students to attribute everything to Pythagoras himself, it is difficult today to determine who actually did which work. To further confuse matters, some forgeries under his name (a few of which still exist) circulated in antiquity. Some of his biographers clearly aimed to present him as a god-like figure, and he became the subject of elaborate legends surrounding his historical persona.

The school that Pythagoras established at Croton was also in some ways a secret brotherhood. It was based on his religious teachings and was highly concerned with the morality of society. Members were required to live ethically, love one another, share political beliefs, practice pacifism, and devote themselves to the mathematics of the Universe. They also abstained from meat, abjured personal property and observed a rule of silence (called "echemythia"), the breaking of which was punishable, based on the belief that if someone was in any doubt as to what to say, they should remain silent.

Pythagoras saw his religious and scientific views as inseparably interconnected. He believed in the theory of metempsychosis or the transmigration of the soul and its reincarnation again and again after death into the bodies of humans or animals until it became moral (a belief he may have learned from his one-time teacher Pherecydes of Syros, who is usually credited as the first Greek to teach the transmigration of souls). He was one of the first to propose that the thought processes and the soul were located in the brain and not the heart.

Another of Pythagoras' central beliefs was that the essence of being (and the stability of all things that create the universe) can be found in the form of numbers, and that it can be encountered through the study of mathematics. For instance, he believed that things like health relied on a stable proportion of elements, with too much or too little of one thing causing an imbalance that makes a person unhealthy.

In mathematics, Pythagoras is commonly given credit for discovering what is now known as the Pythagorean Theorem (or Pythagoras' Theorem), a theorem in geometry that states that, in a right-angled triangle, the square of the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. Although this had been known and utilized previously by the Babylonians and Indians, he (or perhaps one of his students) is thought to have constructed the first proof.

He believed that Arithmology, the number system (and therefore the universe system) was based on the sum of the numbers one to four (i.e. ten), and that odd numbers were masculine and even numbers were feminine. He discovered the theory of mathematical proportions, and also discovered square numbers and square roots. The discovery of the golden ratio approximately 1.618 is also attributed to Pythagoras, or possibly to his student Theano. He was one of the first to think that the Earth was round, that all planets have an axis, and that all the planets travel around one central point, (which he originally identified as the Earth, but later renounced it for the idea that the planets revolve around a central “fire”, although he never identified it as the Sun). He also believed that the Moon was another planet that he called a “counter-Earth".

Pythagoras was also very interested in music, and wanted to improve the music of his day, which he believed was not harmonious enough. According to legend, he discovered that musical notes could be translated into mathematical equations by listening to blacksmiths at work. He also believed in the "musica universalis" (or the "harmony of the spheres"), the idea that the planets and stars moved according to mathematical equations, which corresponded to musical notes and thus produced a kind of symphony.

The tetractys or the tetractys of the decad is a mystical symbol, and it was very important to the secret worship of Pythagoreanism. Tetraktys is a triangular figure consisting of ten points arranged in four rows: one, two, three, and four points in each row, which is the geometrical representation of the fourth triangular number. Number 4 was associated with planetary motions and music:

1. The first four numbers symbolize the musica universalis and the Cosmos as:

- 1) Unity (Monad)

- 2) Dyad – Power – Limit / Infinite (peras / Apeiron in Greek)

- 3) Harmony (Triad)

- 4) Kosmos (Tetrad).

2. 1+2+3+4 add up to ten, which was unity of a higher order (The Dekad).

3. The Tetractys symbolizes the four classical elements—fire, air, water, and earth.

Pythagoras teachings emphasized the immortality and transmigration of the soul (reincarnation), virtuous, humane behaviour toward all living things, and the concept of “number” as truth in that mathematics not only cleared the mind but allowed for an objective comprehension of reality.

There are significant points of contact between the Greek religious movement known as Orphism and Pythagoreanism. There is some evidence that the Orphics also believed in metempsychosis and considerable debate has arisen as to whether they borrowed the doctrine from Pythagoras, or he borrowed it from them. Dicaearchus says that Pythagoras was the first to introduce metempsychosis into Greece (Porphyry). Moreover, while Orphism presented a heavily moralized version of metempsychosis, in accordance with which we are born again for punishment in this life, it is not clear that the same was true in Pythagoreanism. One would expect that the Pythagorean way of life was connected to metempsychosis, which would in turn suggest that a certain reincarnation is a reward or punishment for following or not following the principles set out in that way of life (see also present day beliefs on Karma).

It is crucial to recognize that most Greeks followed Homer in believing that the soul was an insubstantial shade, which lived a shadowy existence in the underworld after death. Pythagoras’ teachings that the soul was immortal, would have other physical incarnations and might have a good existence after death were striking innovations, that must have had considerable appeal in comparison to the older Homeric view.

Whether or not one accepts this account of Pythagoras and his relation to Avaris, there is a clear parallel for some of the remarkable abilities of Pythagoras in his student Empedocles, who promises to teach his pupils to control the winds and bring the dead back to life. There are recognizable traces of this tradition about Pythagoras even in the pre-Aristotelian evidence, and his wonder-working clearly evoked diametrically opposed reactions. Empedocles, on the other hand, is clearly sympathetic to Pythagoras, when he describes him as “a man who knew remarkable things” and who “possessed the greatest wealth of intelligence” and again probably makes reference to his wonder-working by calling him “accomplished in all sorts of wise deeds”.

Pythagoras' influence on later philosophers, and the development of Greek philosophy generally, was enormous. Plato (c. 428/427-348/347 BC) references Pythagoras in a number of his works and Pythagorean thought, as understood and relayed by other ancient writers, is the underlying form of Plato's philosophy. Plato's great student Aristotle (384-322 BC) also incorporated Pythagorean teachings into his own thought and Aristotle's works would influence philosophers, poets, and theologians (among many others) from his time through the Middle Ages (c. 500 -1500 AD) and into the modern day. Pythagoras remains a mysterious figure in antiquity, therefore, he also stands as one of the most significant in the development of philosophical and religious thought.

What is known of Pythagoras comes from later writers piecing together fragments of his life from contemporaries and students. Pythagoras was associated with so many legends that few scholars dare to say much about his life, his personality, or even his teachings, without adding that we cannot be sure our information is accurate. Nevertheless, it is notoriously difficult to distinguish between the teachings of Pythagoras himself and those of his followers, the Pythagoreans.

None of Pythagoras' writings – if he wrote anything – have survived and, owing to the secrecy he demanded of his students, the specifics of his teachings were carefully kept. The philosopher Porphyry (234 - 305 A.D.), who wrote a later biography of Pythagoras, noted:

“What he taught his disciples no one can say for certain, for they maintained a remarkable silence. All the same, the following became generally known. First, he said that the soul is immortal; second, that it migrates into other humans or animals; third, that the same events are repeated in cycles, nothing being new in the strict sense; and finally, that all things with souls should be regarded as akin. Pythagoras seems to have been the first to introduce these beliefs to Greece.”

Whether he concealed his teachings for this reason or some other cannot be ascertained. It is possible he simply felt the masses would not understand or appreciate his ideas. Whatever the reason, the secrecy added greatly to his mystique and reputation. His belief in the immortality of the soul and reincarnation led naturally to a vegetarian lifestyle with an emphasis on doing no harm to any other living thing and this asceticism, which he also demanded of his followers, elevated his reputation as a holy man even further.

Diogenes Laertius describes his diet and habits: He describes Pythagoras as eating fish and sea food, but most other ancient authors maintain he was a strict vegetarian abstaining from the meat of any living thing which could be regarded as having a soul. He likewise abstained from sex and remained celibate to maintain spiritual power and clarity of thought. In disengaging from worldly pleasures such as sex and food, he freed himself from the distractions of the body to focus on the improvement of the soul. This asceticism was thought by some to go too far. He and his followers were known to especially abstain from eating, or even touching, broad beans.

To Pythagoras vegetarianism, pacifism, and humane treatment of other living things were all part of the path to inner peace. By extension, to world peace, in that humans could never live in harmony as long as they killed, ate, and were cruel to animals. He believed that all creatures were created equal and should be treated with respect.

He was considered by contemporaries and later writers as a mystic - not a mathematician as he is sometimes defined in the present day - and his school was associated with spiritual salvation and miraculous revelation. A central belief, which would significantly influence Plato, was that philosophic inquiry was vital to the salvation of the soul and apprehension of ultimate truth. An aspect of that truth was that nothing ever significantly changed and all was eternal and eternally recurring. According to the ancient writer, and student of Aristotle's, Eudemus of Rhodes, Pythagoras believed in eternal recurrence as a logical, mathematical necessity. The concept of the cyclical nature of life and the immortality of the soul were at the heart of Pythagorean thought and influenced many writers and thinkers of ancient Greece but none as significant as Plato.

It is possible that Plato began as a student of Socrates, adhering to dialectic in establishing truth, and then only gradually moved toward embracing the idealism of Pythagoras – as some scholars have claimed – but it seems more probable that Socrates himself was aligned with Pythagorean thought. There is really no way of establishing any claim along these lines since most of what we know of Socrates comes from Plato's Dialogues which were written after Socrates' death when Plato was already of a mature philosophical mind.

Although he was introduced to it, Pythagorean thought significantly influenced Plato's philosophy which included the concept of an ultimate truth not subject to opinion, of an ethical way of living in line with that truth, the soul's immortality, the necessity of salvation through philosophy, and of learning-as-recollection. Pythagorean concepts are apparent throughout Plato's work but most notably in the dialogues of the Meno and Phaedo.

In the Meno, Socrates shows how what one calls “learning” is actually only “remembering” lessons from a past life. He proves his claim by having a young, uneducated slave solve a geometrical problem. Plato argues that, if one dies with one's mind intact, one will 'remember' what one learned during that life when one is born into the next. What one thinks one 'learns' in this life, one is actually only 'remembering' from one's past life and what one knew in that past life was remembered from a previous one.

Plato never addresses the obvious problem with this theory: at some point, the soul must have had to actually “learn” and not just “remember”. Pythagoras' assertion that “things are numbers” and that one could understand the physical world through mathematics also features in the Meno, not only through Socrates' interaction with the slave but through his argument that virtue is a singular quality inherent in all people, regardless of their age, sex, or social status, in the same way that “number” informs and defines the known world; one recognizes reality through a distinction between unity and duality.

To Pythagoras, mathematics was the path toward enlightenment and understanding and, as he claimed, “Ten is the very nature of number” and by this 'number' he meant not only a unit of measurement but a means by which the world could be grasped and understood.

The mathematical proofs Socrates offers concerning even and uneven numbers finally leads to the above proof that “even” cannot admit of the “odd” in order to remain itself (even) and so life (the soul) cannot admit of death and still remain life; therefore, the soul must be immortal. This entire argument typifies Pythagorean thought as understood by ancient writers and practiced by Pythagorean sects of Plato's time.

Pythagoras is said to have assimilated all the knowledge and wisdom of his time and is described as a universal genius who went down in the annals of world history. In order to pass on his knowledge, his wisdom and his skills Pythagoras founded a school in Croton, where persons of high integrity and intellect went forth, characters who were capable of developing humane social systems and of leading the destiny of a country for the welfare of all its subjects. The school at Croton was destroyed under tragic circumstances, but the teachings have never ceased to play their vital role in civilization.

The details of Pythagoras' life may never be fully known but his influence continues to be felt, world-wide, in the present day.

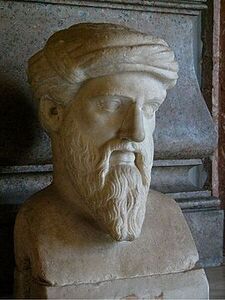

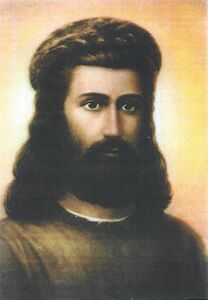

Let me finish by sharing two pictures with you:

|

|

The picture in red frame is from a bust of Pythagoras sculpted in antiquity.

In the second one, I am sure you recognize one of the Mahatmas drawn under the supervision of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the Master Kut Humi Lal Sing. I think the similarity of the figures in these two pictures is obvious.

Thank you.

03/07/2021

Sources used for this lecture:

- World History Encyclopedia: Pythagoras by J.J. Mark, May 2019.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Pythagoras. October 2018.

- www.thebigview.com / The Philosophy of Pythagoras. Aug. 2010.

- Pythagoras and the Delphic Mysteries. June 2011 by Edouard Schure.

- The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library: An Anthology of Ancient Writings Which Relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean Philosophy Paperback. July 1, 1987 by Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie (Compiler, Translator), David Fideler (Editor, Introduction)

- Pythagoras Revived: Mathematics and Philosophy in Late Antiquity Reprint Edition by Dominic J. O'Meara (Author)

- Divine Harmony: The Life and Teachings of Pythagoras. Nov. 1999 by John Strohmeier and Peter Westbrook