A Royal Funeral in Egypt

...

Fig. 27 – Youth

Fig. 26 – Old Age

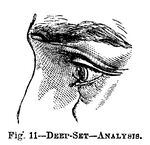

Fig. 11 – Deep-Set – Analysis

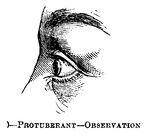

Fig. 10 Protuberant – Observation

Fig. 9 – Prominent – Language

Druidism in Modern Times

Druidism in modern times.—The practice of lighting fires on St John's Eve is clearly Celtic; it prevails throughout Ireland, and there is little doubt that it is a relic of the ancient ire-worship brought by the Celtic immigration from the East, and preserved in a modified form by the Druids. The custom of building churches with the chancel to the East is another manifest relic of heliolatry, and furnishes a striking proof of the tenacity with which people cling to an established observance, even for thousands of years after its spirit and meaning have passed away. The Isle of Man was the central stronghold of Druidism for the three kingdoms, and, as might be expected from its insular position, has preserved many druldical customs. This is satisfactorily proved by Mr. Train in his “Historical and Statistical Accounts of the Isle of Man." We need cite but one example: The Man peasantry never let their fires go out voluntarily, believing that such an event woe id portend some dreadful calamity, an idea in strict conformity with Druidical and Persian notions.—Michael Angola Carver.

The Omnipresence of Life

The omnipresence of life.—It matters little where we go: everywhere—in the air above, in the earth beneath, and waters under the earth—we are surrounded with Life. Avert your eyes awhile from our human world, with its ceaseless anxieties, its noble sorrow, poignant, yet sublime, of conscious imperfection aspiring to higher states, and contemplate the calmer activities of that other world with which we are so mysteriously related. 1 hear you exclaim, “The proper study of Mankind is Man;” nor will I pretend, as some enthusiastic students seem to think, that “the proper study of mankind is cells;” but agreeing with you that man is the noblest study, I would suggest that under the noblest there are other problems which we must not neglect. Man himself is imperfectly known, because the laws of universal Life are imperfectly known. His life forms but one grand illustration of Biology, the Science of Life,* as he forms but the apex of the animal world. . . .

Nature lives; every pore is bursting with Life; every death is only a new birth, every grave a cradle. And of this we know so little, think so little! Around us, above us, beneath us, that great mystic drama of creation is being enacted, and we will not even consent to be spectators! Unless animals are obviously useful or obviously hurtful to us, we disregard them. Yet they are not alien, but akin. The Life that stirs within us stirs within them. We are all “parts of one transcendent whole.” The scales fall from our eyes when we think of this; it is as if a new sense had been vouchsafed to us, and we learn to look at Nature with a more intimate and personal love.

Life everywhere! The air is crowded with birds—beautiful, tender, intelligent birds—to whom life is a song and a thrilling anxiety, the anxiety of love. The air is swarming with insects,—those little animated miracles. The waters are peopled with innumerable forms, from the animalcule, so small that one hundred and fifty millions of them would not weigh a grain, to the whale, so large that it seems an island as it sleeps upon the waves. The bed of the seas is alive with polypes, crabs, star-fishes, and with sand—numerous shell-animalcules. The rugged face of rocks is scarred by the silent boring of soft creatures, and blackened with countless mussels, barnacles, and limpets. Life everywhere!—George Henry Lewes.

* The needful term Biology (from Bios, life, and logos, discourse) is now becoming generally adopted in England as in Germany. It embraces all the separate sciences of Botany. Zoology, Comparative Anatomy, and Physiology.

Some Idea of the Age of the World

Some idea of the age of the world.—In One of the issues of “Nature” Mr. Alfred Russell Wallace indulges in some speculations on the probable antiquity of the human species which may well startle even those who have long since come to the conclusion that six thousand years carry us but a small way back to the original home. In fact, in Mr. Wallace’s reckoning, six thousand years are but as a day. He begins by complaining of the timidity of scientific men when treating of this subject, and points out the fallacy of always preferring the lowest estimate in order to be “on the safe side.” He declares that all the evidence tends to show that the safe side is probably with the large figures. He reviews the various attempts to determine the antiquity of human remains or works of art, and finds the bronze age in Europe to have been pretty accurately fixed at three to four thousand years ago; the stone age of the Swiss Lake dwellings at five to seven thousand years; “and an indefinite anterior period.” The burnt brick found sixty feet deep in the Nile alluvium indicates an antiquity of twenty thousand years; another fragment at seventy-two feet gives twenty thousand years. “A human skeleton found at a depth of sixteen feet below four buried forests, supposed upon each other, has been calculated by Dr. Dowler to nave an antiquity of fifty thousand years.” But all these estimates pale before those which Kent’s Cavern, at Torquay, legitimates. Here the drip of the stalagmite is the chief factor of our computations, giving us an upper floor which “divides the relics of the last two or three thousand years from a deposit full of the bones of extinct mammalia, many of which, like the reindeer, mammoth, and glutton indicate an arctic climate.” Names cut into this stalagmite more than two hundred years ago are still legible; in other words, where the stalagmite is twelve feet thick and the drip still very copious, not more than a hundredth of a foot has been deposited in two centuries—a rate of five feet in one hundred thousand years. Below this, however, we have a thick, much older, and more crystalline (i.e., more slowly formed) stalagmite, beneath which, again, “in a solid breccia, very different from the cave-earth, undoubted works of art have been found.” Mr. Wallace assumes only one hundred thousand years for the upper floor, and about two hundred and fifty thousand for the lower, and adds one hundred and fifty thousand for the intermediate cave-earth, by which he arrives at the “sum of half a million as representing the years that have probably elapsed since flints of human workmanship were buried la the lowest deposits of Kent’s Cavern.”

Editor's notes

- ↑ A Royal Funeral in Egypt by unknown author

- ↑ Fig. 27 – Youth by unknown author

- ↑ Fig. 26 – Old Age by unknown author

- ↑ Fig. 11 – Deep-Set – Analysis by unknown author

- ↑ Fig. 10 Protuberant – Observation by unknown author

- ↑ Fig. 9 – Prominent – Language by unknown author

- ↑ Druidism in Modern Times by Carvey, M. A., Spiritual Scientist, v. 1, No. 3, September 24, 1874, p. 27

- ↑ The Omnipresence of Life by Lewes, G. H., Spiritual Scientist, v. 1, No. 3, September 24, 1874, p. 27

- ↑ Some Idea of the Age of the World by unknown author, Spiritual Scientist, v. 1, No. 3, September 24, 1874, p. 27

Sources

-

Spiritual Scientist, v. 1, No. 3, September 24, 1874, p. 27