Recent Materialistic Speculations Viewed in the Light of Spiritualism

The meeting of the British Association, at Belfast, Ireland, has been signalized by the delivery of remarkable addresses by two great leaders of scientific thought. Profs. Tyndall and Huxley. The conclusion arrived at by Prof. Tyndall may be roughly summarized thus: Matter is the one fact, self-existent and self-contained. Prof. Huxley affirms that man is, or, at any rate, may be, a mere machine. So that these two philosophers have between them reduced things to very simple conclusions. “I,” an individuality, rational, as I imagine, responsible, possessed of mind and soul, capable of contemplating the mysteries of Nature and the operations of Nature’s God, with yearnings after immortality within, and evidences of disembodied life all around,—“I,” and my consciousness, and my aspirations, and my soul, and my immortality,—I am one vast fallacy. The man of science steps forward to enlighten my ignorance, and to lift the veil from my eyes. “I” am a machine, a mere result of Automic Evolution, standing alone in the midst of that which alone exists, and which I have hitherto foolishly supposed to be the product of my own sensations, but which is the one real existent entity, all else being the baseless fabric of a speculative brain. Matter is the one Final Cause: that which alone can be Investigated. Mind, Soul, Spirit, God,—old wives’ fables, cunning speculations, dreamy aspirations at best the outcome of sentimental fancy, or of visionary enthusiasm. There in oar entity, Matter, and Tyndall is its Prophet. Man is an Automatic Machine, and Huxley is the most perfect specimen.

It will be expected that some evidence should be adduced in prowl of the epigrammatic summary which we have ventured In. The proof is not far to seek. After a long resume of the perpetual conflict between science and theology, the Professor goes on to say:—

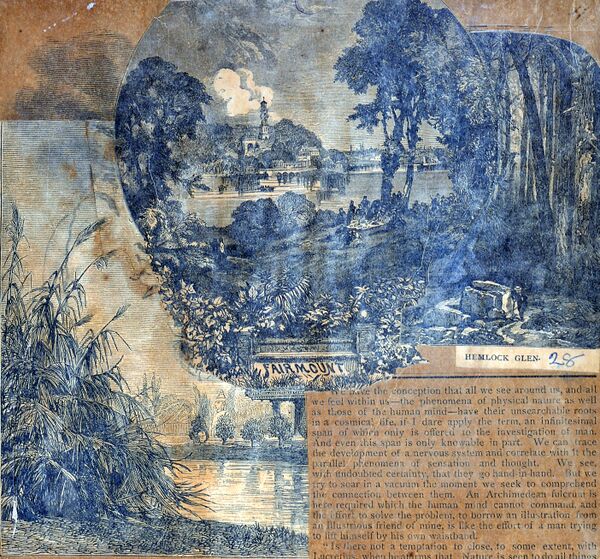

“We have the conception that all we see around us, and all we feel within us—the phenomena of physical nature as well as those of the human mind—have their unsearchable roots in a cosmical life, if I dare apply the term, an infinitesimal span of which only is offered to the investigation of man. And even this span is only knowable in part. We can trace the development of a nervous system and correlate with it the parallel phenomena of sensation and thought. We see, with undoubted certainty, that they go hand-in-hand. But we try to soar in a vacuum the moment we seek to comprehend the connection between them. An Archimedean fulcrum here required which the human mind cannot command, and the effort to solve the problem, to borrow an illustration from an illustrious friend of mine, is like the effort of a man trying to lift himself by his own waistband.

“Is there not a temptation to close, to some extent, with Lucretius, when he affirms that ‘Nature is seen to do all things spontaneously of herself, without the meddling of the gods?’ or with Bruno, when he declares that Matter is not ‘that mere empty capacity which philosophers hare pictured her to be, but the universal mother who brings forth all things as the fruit of her own womb?’ The questions here raised are inevitable. They are approaching us with accelerated speed, and it is not a matter of indifference whether they are introduced with reverence or with irreverence. Abandoning all disguise, the confession that I feel bound to make before you is that I prolong the vision backward across the boundary of the experimental evidence, and discern in that Matter, which we, in our ignorance, and notwithstanding our professed reverence for its Creator, have hitherto covered with opprobrium, the promise and potency of every form and quality of life.”

“Religion, though valuable in itself, is only man’s speculative creation. It Is good for man to frame for himself a theology, if only to keep him quiet.”

“And if, still unsatisfied, the human mind, with the yearning of a pilgrim for bis distant home, will turn to the Mystery from which it has emerged, seeking so to fashion it as to give unity to thought and faith, so long as this is done, not only without intolerance or bigotry of any kind, but with the enlightened recognition that ultimate fixity of conception is here unattainable, and that each succeeding age must be held tree to fashion the mystery in accordance with its own needs, —then, in opposition to all the restrictions of materialism. I would affirm this to be a field for the noblest exercise of what, in contrast with the knowing faculties, may be called the creative faculties of man. Here, however. 1 must quit s theme too great for me to handle, but which will be handled by the lefties t minds ages after you and I, like streaks of morning cloud, shall have melted into the infinite azure of the peat.”

This is a dreary outcome of this blank materialism. We do not use the words as any epithet of reproach. We simply state a truth, however cunningly the introduction of a certain “Mystery” may strive to spiritualize the plain avowal. If the man who avows as his creed a belief In Matter as containing “the promise and potency of every form and quality of life” be not a Materialist, then words have lost their meaning, and a devout believer in Jesus Christ may not fairly be called a Christian. The solitary qualification of this creed that is discoverable throughout the long address, is one that the Profes <... continues on page 5-56 >

Editor's notes

Sources

-

Spiritual Scientist, v. 1, No. 6, October 15, 1874, pp. 61-3